Social Science Research in a COVID-19 World

IPR researchers apply their research, launch new projects to tackle pandemic’s wide-ranging effects

Get all our news

IPR’s strength lies in the diversity of its scholars, who come together across many different fields. Not only are they working on immediate aspects of the crisis in the short-term, but also on fundamental issues that in the long-term will contribute to rebuilding our society and institutions once this crisis is over.”

Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach

IPR Director and Economist

As COVID-19 continues to spread in the U.S. and around the globe, its effects have been wide-ranging and abrupt, throwing untold tens of millions out of work, shutting down societies and economies, shredding healthcare systems and safety nets. For the most part, the world’s attention has been focused on the medical, biological, and epidemiological aspects of the coronavirus, but social science researchers have also been hard at work to understand and address its ravaging effects on society at large, IPR’s interdisciplinary faculty experts among them.

“IPR’s strength lies in the diversity of its scholars, who come together across many different fields,” said IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, an economist. “Not only are they working on immediate aspects of the crisis in the short-term, but also on fundamental issues that in the long-term will contribute to rebuilding our society and institutions once this crisis is over.”

Heeding the Call for Evidence

IPR experts are responding to unparalleled calls from governments, foundations, and citizens for more evidence to answer pressing questions about the virus’ effect on our social, cultural, political, and economic institutions. In speaking with the media, they have already taken on the task of translating and applying their research to myriad issues from unemployment and the social safety net to how the crisis affects childcare and family relationships. Many faculty are in the process of launching or revamping research projects related to various aspects of the virus (see below).

The Institute is also working to reconvene around new and emerging research by revamping its signature Monday colloquium series. IPR Associate Director James Druckman, a political scientist, is leading the effort to create a virtual series highlighting pandemic-related research from faculty in different disciplines. The informal 20–30 minute online presentations will start on Monday, April 13, and the schedule, can be found here.

“Many IPR faculty quickly have pivoted their research to focus on the coronavirus,” Druckman said. “We recalibrated our spring series to highlight this ongoing work and to provide a cross-disciplinary forum for feedback.”

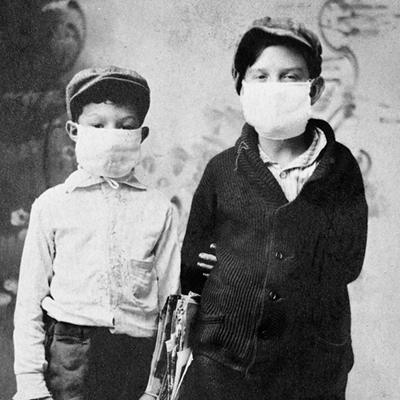

Learning from the Past

IPR researchers have parsed other brutal “shocks,” such as the 1918 influenza pandemic and the Great Recession, tracing their devastating socioeconomic effects over time. Economist and IPR associate Joseph Ferrie and his colleagues compared brothers born in 1919 to those who were born in another year, discovering that those exposed in utero to the 1918 flu had fewer years of schooling and were less likely to graduate from high school. IPR health psychologists Edith Chen and Greg Miller studied the 2009 Great Recession’s effects on African American teens’ health, finding that the longer they experienced economic hardship, the higher their epigenetic aging—that is, their cells look “older” than they are chronologically.

IPR economist Kirabo Jackson and his co-authors examined how recessionary cuts to per-student spending by 10% across all four years of high school reduced students’ likelihood of graduating and lowered their test scores. Racial wealth inequalities also increased, according to research by IPR social demographer Christine Percheski and her colleagues, who discovered that the 2009 recession halved the net worth of the wealthiest African American and Hispanic families.

Faculty researchers are also bringing their expertise to the table in thinking about the lessons and research insights they have taken away from public health crises, like HIV-AIDS. They are expanding discussion and examination of issues related to social disparities and health, communication and media, education and economics, coping and stress, policy and evaluation, law and politics, insurance and medicine, and so many more.

“IPR will continue to cover our faculty’s related research initiatives as long as the epidemic continues,” Schanzenbach said. “As always, you can find these and other articles detailing our faculty’s interdisciplinary, rigorous, and relevant research 24/7 at www.ipr.northwestern.edu.”

Read more about IPR’s latest faculty research initiatives here.

Surveying COVID-19 Impacts • Developing a SARS-CoV-2 Test • Improving Modeling

Increasing Food Security and Safety Net Access • Studying Mortality and Health

Understanding the Impact on Gender Equality • Enabling Effective COVID-19 Responses

Survey on Social and Behavioral Impacts of COVID-19

IPR sociologist Beth Redbird launched a survey in March to ask U.S. participants about how they are experiencing life under coronavirus. The survey contains 125 social and behavioral questions, covering a wide variety of topics, including health and stress, household and institution responses, and social and community engagement. It also covers knowledge of COVID-19, for instance, asking respondents how they use media and how satisfied they are with the information they receive from news outlets. The survey asks about economic outlooks, employers, and job changes due to the coronavirus. Thanks to support from the National Science Foundation, she is randomly sampling between 100 and 200 different respondents each day, using a person’s home county to explore how community actions affect attitudes and behaviors.

Once the survey is complete, Redbird intends to make the anonymized data publicly available for further research. “Often, we are unable to gather data in the middle of significant social disruption, either because the change occurred too quickly or was too disruptive,” she wrote, noting the data could benefit research in other disciplines as well. “This will not be the last event of its kind, but with a thorough understanding of its effects, we can be better prepared for the next one.”

Developing a New Test for SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies

IPR biological anthropologist Thomas McDade is developing a new means of testing for antibodies in SARS-CoV-2, the official name for the virus that causes COVID-19. He is currently pulling together resources and equipment to launch the effort.

The current approach is to detect the virus directly through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using samples collected by swabbing a person’s throat or nose. PCR tests involve tracking the virus’ genome, and the downside is that they are only effective within the window of active infection. Once the infection has cleared, PCR-based tests return negative results.

McDade’s approach will involve using a blood test to identify SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Those antibodies remain in the blood longer once the infection is gone.

“Using such a method should, therefore, allow us to identify ‘cases’ after the fact, independent of clinical diagnosis and symptom experience,” McDade wrote in an email.

His approach relies on his pioneering work to develop field-friendly dried blood spot (DBS) methods, in which drops of whole blood collected from a simple finger stick are stored on special filter paper. This low-cost method makes samples easier to collect and transport and would permit safer and more reliable testing in high- and low-income countries alike. This approach has already been successfully implemented in several population-level surveys.

McDade sees DBS antibody testing as a tool for illuminating transmission dynamics in the community, and for identifying which groups in a population might be at greater risk for contracting the virus. It will also permit empirical evaluation of how well policies like social distancing or closing schools and restaurants are working.

Accounting for All Impacts in COVID-19 Modeling

A March 16 report by Imperial College’s COVID-19 Response Team made waves in the media and had the effect of immediately shifting U.S. and U.K. policies from less invasive mitigation strategies to slow down rates of infection—to far more aggressive suppression strategies to quash the epidemic’s growth. However, IPR economist Charles F. Manski, an expert in decision making, argues that the report’s recommendation for suppression as the preferred policy option was unjustifiable because it was based on flawed modeling.

In an op-ed in Scientific American, Manski points out that the epidemiological model used in the study only accounted for the pandemic’s impact on healthcare systems, ignoring equally critical ethical and economic costs. He offers two reasons for why epidemiological models fail: First, public health and medical experts tend to focus on health, missing how people’s behaviors might affect outcomes. Second, the models are less accurate because they rely on observational data, which are difficult to interpret and less robust than data from randomized trials.

Manski suggests that one solution to improve modeling might lie in following the lead of climate scientists, who over the past 30 years have worked with economists to develop integrated assessment models. While still lacking, they have improved, and he points to the interdisciplinary method of collaboration as a plus, offering that “Climate researchers and epidemiologists alike should work to improve the credibility of their modeling.”

Firming Up Food Security and the Social Safety Net

IPR Director and economist Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach and the Hamilton Project’s Lauren Bauer (PhD 2016), recommend policymakers take strong steps to firm up the social safety net given the damage the coronavirus pandemic has done to the economy. They point out the stabilizing effects that programs like the Supplementary Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) have not just on families, but on the economy as they increase collective demand for goods.

Schanzenbach and Bauer recommend that Congress and the Trump administration suspend work requirements for SNAP nationwide, give states extra flexibility in determining who is eligible for benefits, increase overall benefit levels, and introduce a multiplier that will give extra benefits to families with young and school-age children. They also advise the government to expand the “Summer EBT” program, a summer food stipend for children eligible for free and reduced-price school meals, to the school year.

With these recommendations, Schanzenbach builds on research she and Berkeley’s Hilary Hoynes conducted for a 2019 report, Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy. Many of the recommendations have been adopted in various forms.

Easing Access to the Safety Net

The expansion of social insurance programs through the recently enacted $2 trillion economic rescue plan will not, on its own, be sufficient to help as many Americans as possible, IPR economist Matthew Notowidigdo and MIT’s Amy Finkelstein write in an op-ed in Governing. They propose two evidence-based steps to enroll more people in need in programs such as unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps.

The expansion of social insurance programs through the recently enacted $2 trillion economic rescue plan will not, on its own, be sufficient to help as many Americans as possible, IPR economist Matthew Notowidigdo and MIT’s Amy Finkelstein write in an op-ed in Governing. They propose two evidence-based steps to enroll more people in need in programs such as unemployment insurance, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps.

First, provide information to people about the programs they may use. The authors’ randomized evaluation on SNAP enrollment showed that when eligible households received informational mailings, nearly twice as many signed up. When assistance with the application was added, enrollment tripled. Other studies also find evidence that reminders and application assistance boost enrollment in safety-net programs.

Second, the researchers recommend clearer eligibility criteria and simplified forms for applicants. They cite the example of the simple one-page application, approved at any point of care, for Disaster Relief Medicaid after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. It worked well to provide coverage for New Yorkers who needed medical care.

Notowidigdo and Finkelstein urge policymakers to get information out to people and to simplify access to critical assistance.

Studying Effects on Mortality and Health

IPR economist Hannes Schwandt studies how the spread of disease and economic crises can have an impact on people’s health as well as acquiring skills and education. His research has direct relevance to the current pandemic.

Schwandt examined children born to mothers who had strong cases of seasonal flu during pregnancy. Using Danish administrative data, he discovered that short-term effects on newborns, such as being born prematurely and low birth weight, are followed by long-term declines in earnings and substantial increases in welfare dependence.

Currently, he is expanding this research looking into the social drivers of infectious-disease spread, examining how families with young children can act as “disease hubs.” He explores how infants’ exposure to infectious disease can affect their getting sick, as well as their skill development and education as they grow up.

Schwandt also analyzes the impact of deep economic contractions, such as the one expected from the current pandemic. He found that cohorts graduating during a recession experience persistent income losses, lower fertility, and a shorter lifespan. He also shows that in times of collapsing stock markets, retirees who have invested heavily in stocks face increases in high blood pressure and heart disease.

Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality

The economic downturn caused by COVID-19 has implications for gender equality, according to a new IPR working paper by economist and IPR associate Matthias Doepke. He and his colleagues show that while job losses were higher for men in past recessions, the COVID-19 pandemic has shut down restaurants and slowed travel, impacting industries that employ many women.

Closing schools and daycare centers has also increased the need for childcare dramatically, and time-use studies indicate that women will provide most of this additional childcare. Together, these factors indicate that COVID-19 will have a disproportionately negative effect on women, especially single mothers or families that cannot combine work with caring for children at home.

The researchers also point out that the crisis presents opportunities to promote gender equality during the recovery. More employers will offer flexible work arrangements such as work-from-home options, which will benefit women because they tend to combine work and childcare. Additionally, many fathers will also take on more childcare responsibilities, especially those whose spouses have jobs such as doctor or nurse that are essential during pandemic. Such changes may lead to more equality in the division of childcare and housework between women and men as well as producing long-term effects on expectations in society for how women and men are supposed to act.

Shifting Resources and Research to Effective COVID-19 Responses

Development economist and IPR associates Dean Karlan and Chris Udry, who direct the Global Poverty Research Lab at Northwestern, are collaborating with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), founded by Karlan in 2002, to launch Research for Effective COVID-19 Responses, or RECOVR. IPA, which has offices in 22 low-income countries around the world, will shift all of its expertise in collecting data, evidence, and analysis to initiatives that will better equip leaders in vulnerable countries to make more informed decisions about COVID-19.

RECOVR’s goals include reducing transmission of the coronavirus, learning what messaging strategies best influence social distancing practices, tracking levels of economic activities and hygiene practices, tracking how vulnerable households are coping, and assessing how rapid-fire social protection strategies such as supplementary cash transfers can help households cope.

IPA has moved all their data collection to phone surveys. Along with collecting data, IPA is working with local governments to get them the data and analysis they need to set needed public health recommendations and policies.

For more information about these and other IPR faculty experts’ research, please visit IPR’s website and IPR’s COVID-19 research and media webpage.

Photo credits: iStock; Flickr: State and Library Archives of Florida; CDC/ Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAMS; Pexels

Published: April 8, 2020.