COVID-19 Magnifies Racial Disparities in Health

IPR researchers heed the call for data and policy perspectives

Get all our news

We are seeing dramatic inequities in the risk of infection, and the risk of death, across the U.S. and especially in Chicago. There is an urgent need for community-based research on the origins of these inequities to inform policies that can effectively mitigate future outbreaks.”

Thomas McDade

IPR biological anthropologist and director of Cells to Society (C2S): The Center on Social Disparities and Health

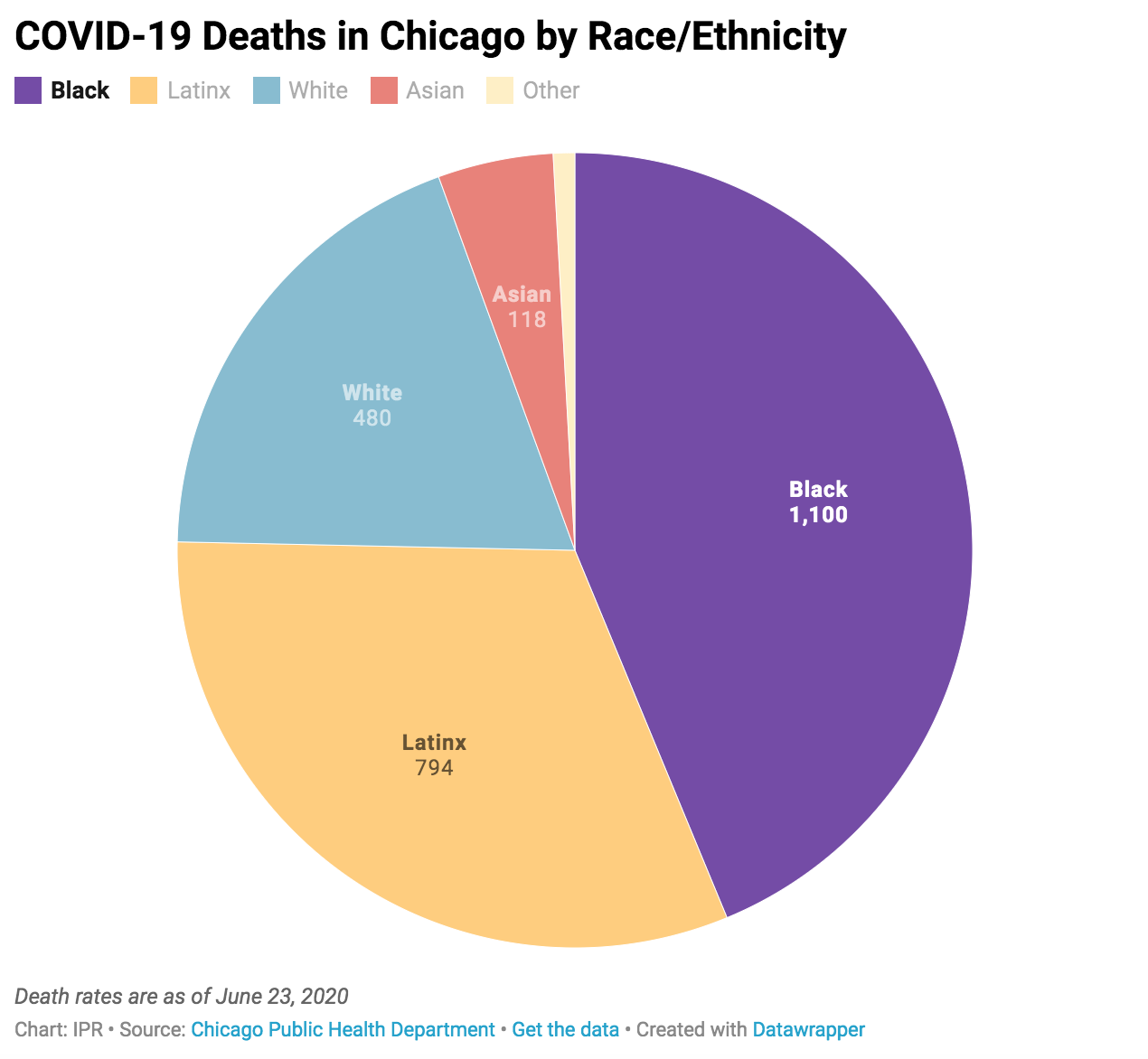

Only 30% of Chicago’s residents are African American, yet as of late June they comprise 44% of those who have died from COVID-19, according to Chicago’s Department of Public Health. Both African American and Latinx residents are also getting sick from COVID-19 at higher rates than White residents.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot addressed the city’s alarming racial disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths at a press conference on April 6, saying “This is a call-to-action moment for all of us. When we talk about equity and inclusion, they’re not just nice notions—they are an imperative that we must embrace as a city.”

For many who study health and social disparities and who are seeing similar numbers across America, including IPR researchers, the call is already being heeded.

“We are seeing dramatic inequities in the risk of infection, and the risk of death, across the U.S. and especially in Chicago,” said IPR biological anthropologist Thomas McDade, who directs IPR’s Cells to Society (C2S): The Center on Social Disparities and Health. “There is an urgent need for community-based research on the origins of these inequities to inform policies that can effectively mitigate future outbreaks.”

Two national surveys also underscore the magnitude of the issue: CoronaData U.S., led by IPR sociologist Beth Redbird, reveals that African American and Asian American families have been hit particularly hard, with nearly 1 in 10 having a family member with COVID-19. IPR political scientist James Druckman is part of a 50-State COVID-19 Survey showing that African American, Asian American, and Hispanic respondents’ worries about getting the virus were at least 12 points higher (>70%) than for White respondents (58%).

A Pioneering Approach to Understanding Health Disparities

Since its founding in 1968, another significant period of social unrest, IPR’s researchers have tackled disparities in many insidious and persistent forms, whether racial, wealth, gender, education, social, health, or others.

In 2007, a new generation of IPR researchers came together, with unique expertise in emerging academic areas like “psychobiology” or “biological anthropology.” Their idea was to bring together the social, life, and biomedical sciences to study how social, racial, and economic disparities “get under a person’s skin.” To do this, they founded C2S, which McDade now directs, as a catalyst for probing how these social connections matter to human health and development.

Their research relies on innovative biological and other traditional measures to understand how a person’s environment and experiences at home, at school, at work, and even before being born, can have long-lasting effects that shape health and opportunities across a life. Below are studies that highlight this interdisciplinary work and how they might apply to better understanding the impact of COVID-19.

Antibody Testing and Disparities | Discrimination and Health | Financial Debt and Health

Economic Downturns and Health | Racial Bias in Medicine | Collaboration for Health Equity

Antibody Testing to Help Map Disparities in COVID-19

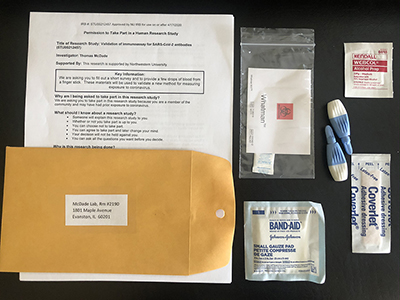

Understanding the underlying causes of the racial and social disparities in disease outcomes is still a critical work in progress. For example, it is not yet exactly known how many people have been exposed to the virus, the actual death rate, or the true effectiveness of policies like social distancing. Testing is key to this understanding, and McDade is working with colleagues to roll out a new at-home test for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The method uses a single drop of blood collected from a simple finger prick. It offers the advantage of allowing people to test in their homes and then mail the sample to a lab for analysis. He is working with medical school faculty and IPR associate Brian Mustanski, professor of medical social sciences, to recruit participants from across Chicago’s neighborhoods on a “no contact” platform to examine the origins of social inequities in COVID-19.

Understanding the underlying causes of the racial and social disparities in disease outcomes is still a critical work in progress. For example, it is not yet exactly known how many people have been exposed to the virus, the actual death rate, or the true effectiveness of policies like social distancing. Testing is key to this understanding, and McDade is working with colleagues to roll out a new at-home test for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The method uses a single drop of blood collected from a simple finger prick. It offers the advantage of allowing people to test in their homes and then mail the sample to a lab for analysis. He is working with medical school faculty and IPR associate Brian Mustanski, professor of medical social sciences, to recruit participants from across Chicago’s neighborhoods on a “no contact” platform to examine the origins of social inequities in COVID-19.

Racial Discrimination Can Lead to Worse Health

When levels of cortisol, the hormone associated with stress, remain flat throughout the day, a slew of negative health consequences follow, including a weakened immune system that could leave one more susceptible to deadly viruses like COVID-19. Consistently flat cortisol levels have been linked to increased risks for fatigue, cancer, depression, and obesity, as well as various autoimmune disorders. In one study, IPR developmental psychobiologist Emma Adam and her fellow researchers measured cortisol levels in 120 Black and White adults, collecting self-reports of their perceived racial discrimination (PRD). For Black adults, the researchers showed higher reported discrimination predicted lower and flatter daily cortisol levels. Thus, the extra stress and dysregulated cortisol levels associated with racial discrimination might place individuals of color at a higher risk for worse health. It remains to be seen if these also play a role in higher case and death rates from COVID-19, but Adam does point to a lack of access to healthcare and other structural forms of discrimination as likely contributors.

Adam is currently studying how to adapt existing studies and create new ones to capture how COVID-19 is affecting adolescents during a pandemic. She is also examining application of existing knowledge on adolescent stress and health for creating evidence-based recommendations to improve their mental and physical health.

How Social Stratification Affects Stress and Health

As the U.S. economy continues to reel with massive rises in food insecurity and unemployment, affecting the most vulnerable Americans, IPR researchers are exposing how social stratification is linked to stress and health. McDade was part of a study that was the first to examine the effect of debt on physical health. The results found that a higher debt-to-asset ratio was associated with higher perceived stress and depression, higher diastolic blood pressure, and worse self-reported general health. Another project is now examining how housing and neighborhood quality affect child health. Both studies build on McDade’s investigations of how socially patterned environments in infancy contribute to social disparities in adult health outcomes. With debt levels and homelessness both rising due to COVID-19, these studies could offer important insights into how the disease could affect health and wellbeing.

Economic Downturns Worsen the Poorest Teens’ Health

What is the effect of an economic downturn like the one we are in now on health? IPR health psychologists Edith Chen and Greg Miller have examined how the Great Recession affected health of young African Americans in rural Georgia. They first compared the health of 330 African American teens from low-income families before and after the recession in 2007 and 2010 at ages 16 and 19 respectively. In addition to collecting self-reports on their health, the researchers measured how fast cells age (epigenetic aging) and chronic stress. Both of these increase risk for diseases, such as heart disease or diabetes. The researchers could then link health outcomes to household wealth. Those who lived in stable, low-income households had the best health, while those in households that slipped from low-income to poverty status were worse off. But health was worst for those young people who lived in poverty at the start of the recession and then sank even deeper into it afterwards. Results from a later study at age 25 showed similar patterns. Miller says the study shows how economic conditions and health are interrelated and why policymakers should consider creating programs to monitor cardiovascular health. It also means making sure that those most exposed to economic hardship can be physically active and have access to healthy, affordable food during shelter-in-place orders.

Racial Bias in Medicine Can Affect Treatment

Psychologist and IPR associate Sylvia Perry studies racial bias in medicine, and her work has direct implications for the racial disparities around COVID-19. In a recent study, Perry and her colleagues surveyed 164 doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals in the U.S. and France, finding that American healthcare workers viewed White patients as more personally responsible for their health and more likely to adhere to doctor’s recommendations, relative to Black patients. French healthcare workers did not display significant racial bias toward patients. In the same way, Perry explained, some in healthcare blame racial minorities for what they assume are risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19. Perry said that medical practitioners must instead recognize structural racism at work, which “manifests in ways such as less access to care, greater underlying health conditions, and greater discrimination when they seek out care.” Biased beliefs among healthcare workers could influence whether minority patients seek a diagnosis or make them fearful about how they will be perceived if they test positive for COVID-19.

Druckman has similar findings from a study of minority college athletes who have suffered injuries. His study reveals that given injuries of equal severity, the sports medical staff surveyed believed that Black athletes experienced less pain than White athletes. Druckman and his co-authors suggest the results could be used as a “starting place” for educating all medical workers about how social class, and the hardship it conveys, does not make one impervious to physical pain.

A Collaborative Partnership to Move Toward Health Equity

In addition to mapping how environments and health are linked, IPR researchers are also finding ways to recast structures that can stand in the way of achieving health equity. The Center for Health Equity Transformation (CHET) was established in 2018 under the directorship of health scholar and IPR associate Melissa Simon to build research infrastructure, conduct workforce development, and work closely with community partners to advance health equity. One of its initiatives to address inequity is the Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative (ChicagoCHEC), a community-academic partnership. Founded by Simon and community health scholar and IPR associate Joe Feinglass with colleagues at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Northeastern Illinois University, the collaborative is designed to break down what Simon calls “how we do business” and create a more equitable structure for cancer prevention and treatment in the city and beyond. Simon describes one approach to changing the usual top-down academic to community structure as “elevating” community partners’ status in implementation research to “citizen scientists.” She sees the collaborative as an opportunity to transform the architecture of U.S. healthcare by addressing social determinants of health and bringing talented low-income and minority students into the health professions. This focus on the needs of Chicago’s most distressed and marginalized communities encompasses culturally sensitive and empowering approaches to social distancing, stay-at-home orders, and hygiene guidelines crucial to these communities that have been hardest hit by COVID-19.

Find out more about these and other related studies by C2S and IPR faculty.

Photo credits from top to bottom: iStock, T. McDade, Pexels

Published: June 25, 2020.