Infographic: How Babies' Environments Lead to Poor Health Later

IPR anthropologist Thomas McDade shows how bodies 'remember' experiences

Get all our news

Click on the image above to see a larger version of the infographic.

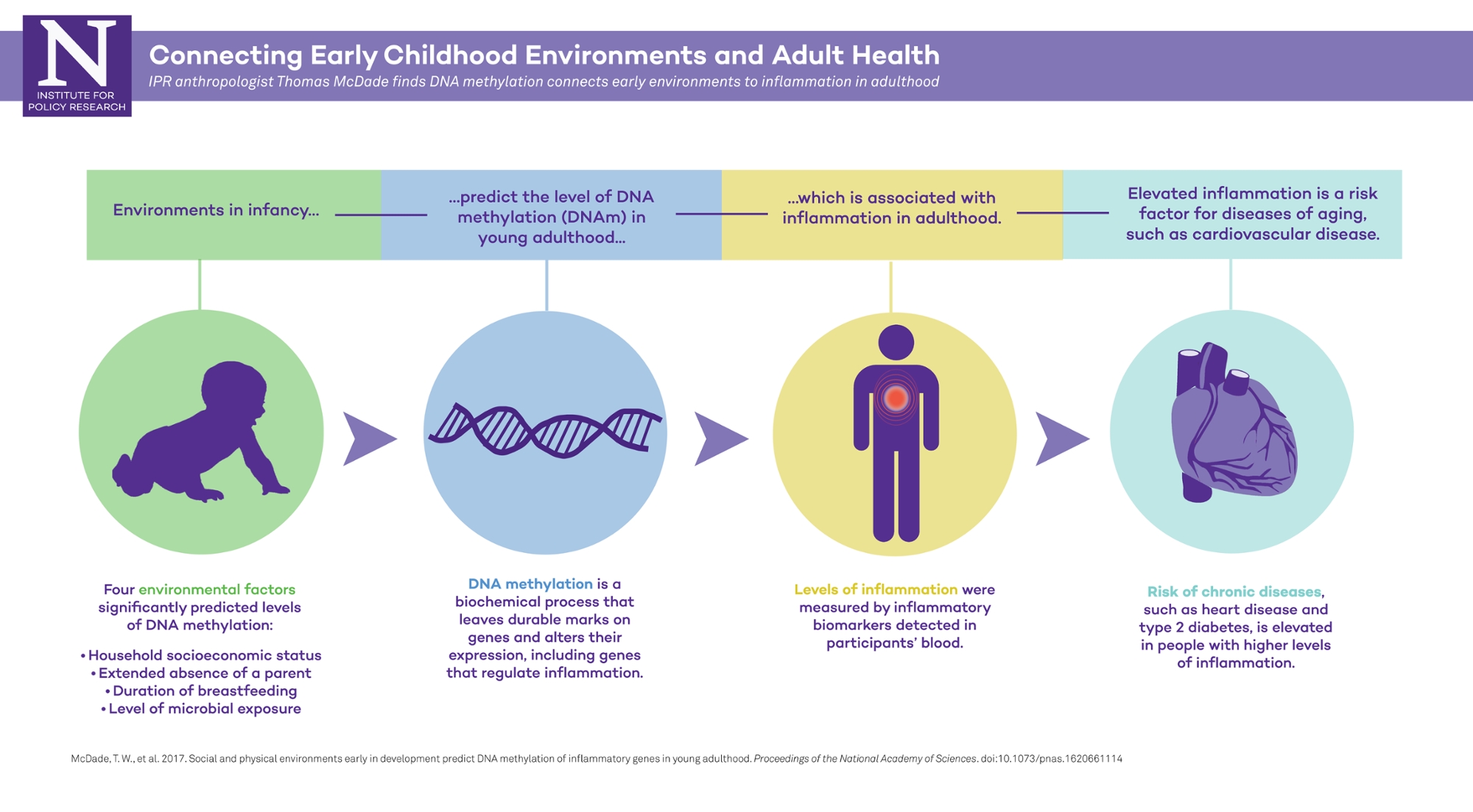

New research, led by IPR scholars, underscores how environmental conditions early in development can cause inflammation in adulthood—an important risk factor for a wide range of diseases of aging, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and dementia.

Drawing on prior research that links environmental exposures to inflammatory biomarkers, the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, breaks new ground in helping to understand how our bodies “remember” experiences in infancy and carry them forward to shape inflammation and health in adulthood.

Using data from a large birth cohort study in the Philippines, with a lifetime of information on the study participants, the researchers find that nutritional, microbial, and psychosocial exposures early in development predict DNA methylation (DNAm) in nine genes involved in the regulation of inflammation.

IPR anthropologist Thomas McDade, who led this study, and his colleagues, including IPR health psychologist Greg Miller, IPR anthropologist Christopher Kuzawa, and two Northwestern graduate students, focused on DNAm—an epigenetic process that involves durable biochemical marks on the genome that regulate gene expression—as a plausible biological mechanism for preserving cellular memories of early life experiences.

In other words, epigenetic mechanisms appear to explain—at least in part—how environments in infancy and childhood are “remembered” and have lasting effects on inflammation and risk for inflammation-related diseases.

“Taking this a step further, the findings encourage us to reconsider the common view that genes are a ‘blueprint’ for the human body—that they are static and fixed at conception,” McDade said.

The research suggests that altering aspects of the nutritional, microbial, and psychosocial environment early in development can leave lasting marks on the epigenome, with the potential to reduce levels of chronic inflammation in adulthood.

Environmental exposures that leave their mark on the epigenome and shape inflammation over the course of development include breastfeeding duration, microbial exposure, socioeconomic status, and the extended absence of a parent.

“If we conceptualize the human genome as a dynamic substrate that embodies information from the environment to alter its structure and function, we can move beyond simplistic ‘nature vs. nurture’ and ‘DNA as destiny’ metaphors that don’t do justice to the complexity of human development,” McDade explained.

Thomas McDade is Carlos Montezuma Professor of Anthropology, director of IPR’s Cells to Society: The Center on Social Disparities and Health, and an IPR fellow. Greg Miller is professor of psychology, co-director of the Foundations of Health Research Center and an IPR fellow. Christopher Kuzawa is professor of anthropology and an IPR fellow.

McDade, T., C. Ryan, M. Jones, J. MacIsaac, A. Morin, J. Meyers, J. Borja, G. Miller, M. Kobor, and C. Kuzawa. 2017. Social and physical environments early in development predict DNA methylation of inflammatory genes in young adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620661114.

Read more from Northwestern News.

Published: July 5, 2017.