Exploring COVID-19’s Impact on Politics

Virtual workshop details effects on political engagement and racial attitudes

Get all our news

One of the things that happens in critical junctures is because we're willing to question even unrelated institutions that often narratives then spark our interest in reform. In this particular instance, the narrative that evolves is the high-profile media story about the murder of George Floyd.”

Beth Redbird

Assistant Professor of Sociology and IPR Fellow

COVID-19 took center stage at the 14th annual Chicago Area Social and Political Behavior Workshop, hosted virtually on July 10.

“We altered the program to focus on COVID-19 and matters of inequality,” said IPR political scientist James Druckman told the more than 110 attendees at the start of the workshop. “My motivation here is to show how our own work can shed light on ongoing events and make clear that social science provides crucial insights into politics and society.”

Two social scientists, IPR sociologist Beth Redbird and Princeton political scientist LaFleur Stephens-Dougan, gave keynote talks on how the pandemic is affecting attitudes around political engagement and racial disparities.

Druckman also organized virtual mentoring sessions, as well as a panel on launching and managing an academic career during a pandemic.

Political Engagement at a Critical Junction

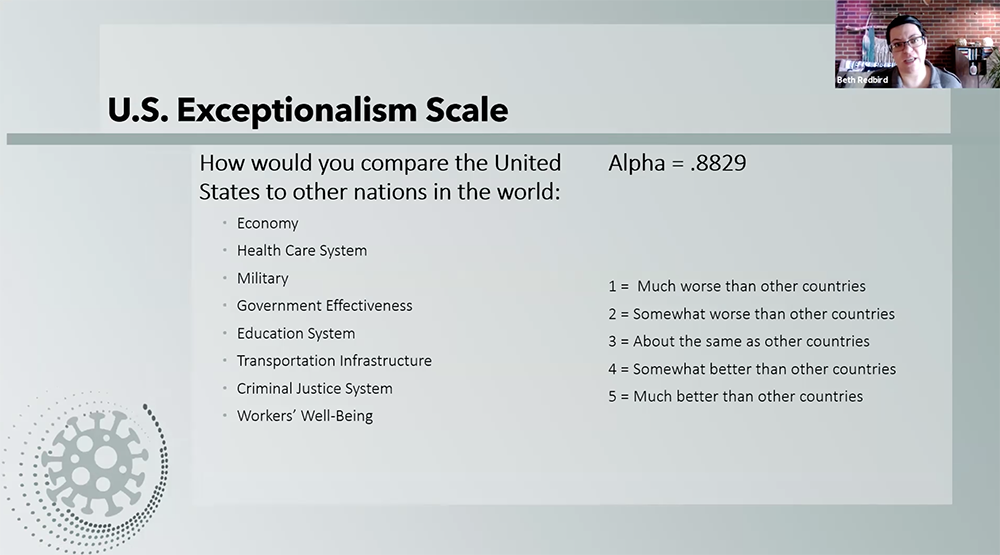

Redbird discussed what a national survey she is leading on attitudes and behaviors during COVID-19 has to say about political engagement and whether Americans are questioning critical institutions during a time of national uncertainty.

According to the survey, Americans’ belief in U.S. exceptionalism has declined compared to other countries when it comes to institutions such as healthcare and the economy. Even institutions seemingly unaffected by the pandemic, such as the military and the criminal justice system, took a hit.

When institutions fail, people look to political parties for answers, Redbird said. Throughout the pandemic, Americans have developed more negative attitudes about the Republican Party, while attitudes about the Democratic Party have remained stable.

“The consequences of this, is that when a crisis of failure comes, we sometimes get this turning point or  openness to change in which we're willing to question the status quo and institutional responses that once seemed really natural or taken for granted are suddenly questioned,” Redbird explained.

openness to change in which we're willing to question the status quo and institutional responses that once seemed really natural or taken for granted are suddenly questioned,” Redbird explained.

She calls this a critical juncture or a point of uncertainty that facilitates institutional change that often begins when faith declines in institutions.

“One of the things that happens in critical junctures is because we're willing to question even unrelated institutions that often narratives then spark our interest in reform,” Redbird said. “In this particular instance, the narrative that evolves is the high-profile media story about the murder of George Floyd.”

Redbird said for sustained institutional change to happen, there must be a short timeframe between the crisis and the ability to make change and people must feel like they have the opportunity to make an impact. An election year provides that opportunity.

“We are definitely in the United States situated in a very opportunistic point to see whether or not a kind of classic critical juncture can make change because there is a mechanism right here, custom made for us, to demand that change,” Redbird argued.

White Americans’ Reactions to COVID-19 Racial Disparities

Early in the pandemic, it became clear there were racial health disparities in coronavirus cases and deaths, with Black Americans being especially vulnerable.

“Racial attitudes seem to be increasingly informing White Americans partisanship,” Stephens-Dougan said in her talk. “We know after Obama's initial first term or post 2008, non-college educated White Americans who were racially resentful were more likely to sort into the Republican Party from the Democratic Party.”

She cited a study showing White people were more supportive of capital punishment when they were told that  it disproportionately affected Black people. To understand if similar support existed in terms of coronavirus racial disparities, she launched two surveys.

it disproportionately affected Black people. To understand if similar support existed in terms of coronavirus racial disparities, she launched two surveys.

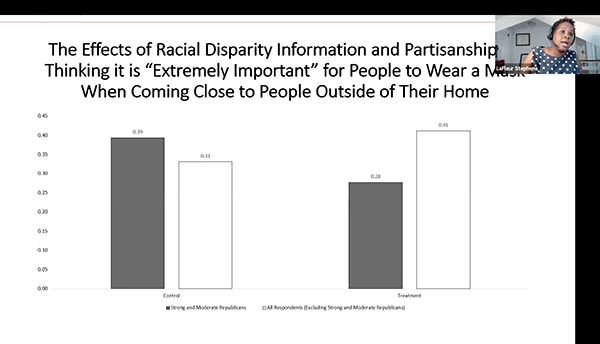

In the first, Stephens-Dougan surveyed 350 White Americans in April—both Democrats and Republicans. Certain participants were randomly assigned to a group where they were told Black Americans were dying from COVID-19 at higher rates than White Americans.

She found that hearing such information led strong and moderate White Republicans to become less supportive of three key areas: non-essential businesses remaining closed, punishment of risky behaviors, and “reopening the economy” protesters staying at home.

In a second nationally representative online survey of 600 White Democrats and Republicans in May, she asked Democrats and Republicans to rank questions related to COVID-19, and again randomly selected participants to receive information about racial disparities in coronavirus cases and deaths. It returned similar results, showing “fairly strong evidence of a racial backlash effect,” she said.

“I think it's fair to say that previous research may have overlooked the influence of race in some of the partisan divisions that we have seen over public health,” Stephens-Dougan said. “And there might be limited political will on the right to address public health crises that disproportionately affect Black people.”

Working in a Changing Environment

To end the conference, Druckman moderated a panel of political scientists that provided advice for young scholars. It included Katherine Cramer of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, David Peterson of Iowa State University, Thomas Rudolph of the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, Alvin Tillery of Northwestern University, and Christina Wolbrecht of the University of Notre Dame. The panelists discussed working conditions during COVID-19, the job market, inclusion of minority scholars, and studying race within political science.

Tillery, who founded the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy at Northwestern, encouraged students and young scholars to research race and politics and ignore accusations of bias.

“I don’t really know any scholars of color who aren’t motivated by a desire to change the structure of racial inequalities,” Tillery said, noting that he was an activist before becoming a scholar and still considers himself to be one through his work.

On a similar note, Wolbrecht said that political science would be better as a discipline if scholars would take advantage of the wisdom and insight of women and minority researchers by citing their work and welcoming them to their departments.

“That sort of change consciousness is something that White scholars really need to think about,” she said.

James Druckman is the Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science and IPR Associate Director. Beth Redbird is assistant professor of sociology and an IPR fellow. LaFleur Stephens-Dougan is assistant professor of politics at Princeton University.

Published: August 3, 2020.