Examining Tribes’ Sovereignty Through Their Constitutions

IPR’s Beth Redbird is leading a research team to catalogue and analyze Native American tribal constitutions

Get all our news

These documents, like most components of Indian life, have been weaponized. They should be put out there so that people who read them understand the trade-offs and nuances the tribes were forced to make.”

Beth Redbird

IPR sociologist

In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in McGirt v. Oklahoma that nearly half of eastern Oklahoma is on an Indian reservation, and crimes committed on that land involving Native Americans had to be prosecuted by either tribal or federal courts. In 2022, the court narrowed their previous ruling in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, giving power over criminal prosecutions of non-Native Americans who are accused of committing crimes against Native Americans back to the state.

The decision's reversal represented more than a shift in the court’s political ideology—it was also part of a long debate over Native American tribal sovereignty and the legal rights the tribes' constitutions gave them. One of the legal justifications Oklahoma officials used to bring their case was that the tribes had not done enough to create a legal system capable of handling criminal cases.

“Indian tribes had lost a right because they had failed to write it in an appropriate way [in their constitutions],” IPR sociologist Beth Redbird said. “And it's not the first time that the structure and manner of these documents have been weaponized to take things from tribes.”

Creating a Database of Native American Constitutions

Several years before either case came before the Supreme Court, in the summer of 2018, Redbird and two IPR Summer Undergraduate Research Assistants began collecting a few Native American tribal constitutions for a research project on the economic development of tribes. Redbird eventually realized there was not a large database of tribal constitutions anywhere in the United States.

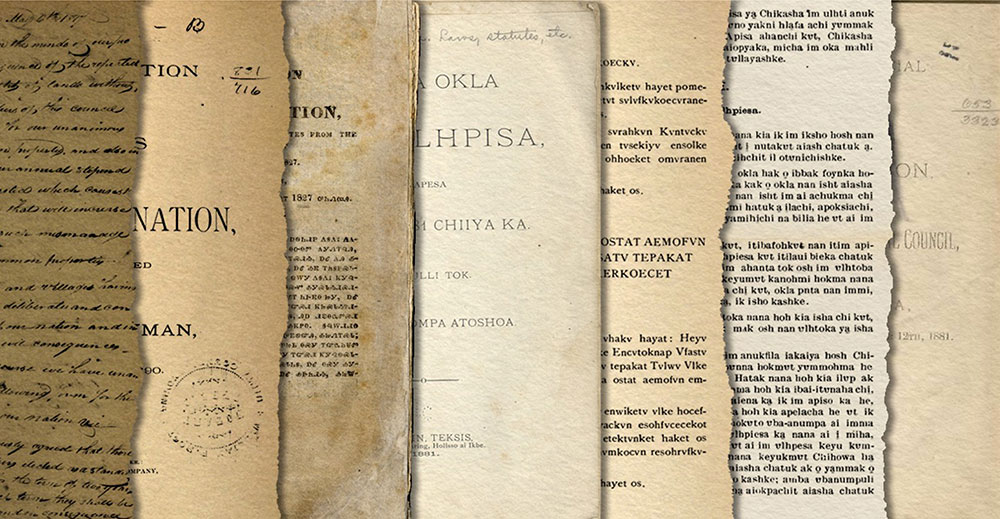

Five years later, Redbird co-leads the Tribal Constitutions Project with Northwestern law professor Erin Delaney, who studies the formation of constitutions under colonialism, to understand the content of tribal constitutions and how they were created. With support from the National Science Foundation, the project now includes over 1,000 North American tribal constitutions and associated documents written between 1934 and 2020. Redbird estimates that her team has been able to locate about 80% of all tribal constitutions.

The U.S. government officially recognized tribal constitutions in 1934 when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) into law, which acknowledges the right of Native Americans to form nations. Prior to this, tribes were prevented from forming governments for several decades, and it was a crime for tribes to elect political leaders.

“One of the key components [to form a government] is that a tribe had to file a written constitution document,” Redbird said. “What's not really known from a legal history standpoint is exactly what that meant and the consequences of that for tribal governments.”

One of the goals of the project is to understand these constitutions both as legal and historical documents. Law students from the NYU-Yale American Indian Sovereignty Project are collaborating with Redbird and Delaney to help code the documents, while Northwestern computer science students in the master’s AI and machine learning program are analyzing the texts.

Tribal Agency or Colonial Constraint?

An ongoing debate about these documents is how much control tribes had over the structure and content of their constitutions because they had to be approved by the Department of the Interior. Redbird says earlier constitutions from the 1930s and 1940s were created from a standard template, which raises questions about whether the IRA represented an opportunity for tribal sovereignty—or if it was another form of colonialization limiting tribal governments’ power.

While Delaney is focused on these questions, Redbird is most interested in the consequence of the structure of the constitutions, or how tribes asserted control through their constitutions, and the outcomes of asserting sovereignty over certain aspects of their lives.

Redbird says a constitution cannot be viewed as a complete statement of tribal sovereignty. At the same time, tribes were able to express some of their values through their constitutions, especially after the Department of the Interior stopped requiring that tribes get permission to edit them under the Obama administration.

“You have agency within this colonial constraint,” Redbird explains, pointing to the documents’ complexity.

Tribal constitutions were collected from a variety of sources, including directly from tribes, library databases, such as the University of Arizona and National Indian Law Library, and archival legislative reports.

While Redbird and her team are still in the process of cataloguing the constitutions, she finds patterns in constitutions written during different periods of Native American law. What tribes passed in their constitutions was more constrained or expansive based on how much freedom tribes had to create governments during the 20th century.

Preserving Constitutions for Future Generations

This project is particularly relevant now, Redbird says, because the population of Native Americans in the United States is growing, according to the 2020 Census, even though tribal populations are shrinking. Other evidence suggests that there are more Native American children living today than in the last 100 years. While the differences in data remain a mystery, Redbird says keeping records of the constitutions is critical as tribal governments continue to evolve and Native populations increase.

“That means that tribes are in the next 10 years or so primed to start revising constitutions to ask questions about who they are as a people,” she said. “Where these documents start can very much influence where they go.”

But without access to other constitutions, it can be difficult for tribes to know how other tribes are creating effective policy. There still is no large federal source containing every Native American tribal constitution.

“It can make being a government and trying to pass policy complex when you have a large amount of invisibility around what your peer nations are doing, and how things function and what works and what doesn't,” Redbird said.

Eventually, the constitutions will be analyzed in legal studies and social science research, and shared more widely with the public as legal documents and through classroom curriculum for K–12 students. Redbird says the constitutions should be shared with context about how they were formed, including oral narratives or tribal statements about what people remember about the passage of these documents.

“These documents, like most components of Indian life, have been weaponized,” Redbird said. “They should be put out there so that people who read them understand the trade-offs and nuances the tribes were forced to make.”

Beth Redbird is assistant professor of sociology and an IPR fellow.

Graphic courtesy of the NYU-Yale American Indian Sovereignty Project.

Published: January 16, 2024.