Labor Unions Are Key in Protecting Workers’ Rights in States

Research suggests that states with more union members maintained better work conditions and offered workers more protections, despite a period of steep decline

Get all our news

Notwithstanding their many inadequacies, employment laws constitute some of the only institutional protections workers have left to defend against exploitation. Their construction over the last 60 years ought to be considered one of organized labor’s most significant and durable legacies.”

Daniel Galvin

IPR political scientist

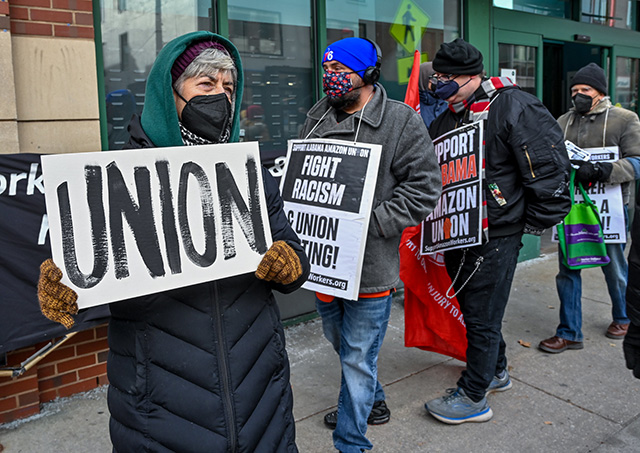

A group of protestors rallied in support of Amazon workers and unionization on January 15, 2022, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Workers at Starbucks, Chipotle, Amazon, REI, Trader Joe’s, and Apple have been unionizing in a wave of recent landmark victories for unions in the retail and restaurant sectors. But for decades, labor union membership in the United States has been falling, with private sector union membership declining from 24.2% in 1973 to 6.1% by 2021.

Research by IPR political scientist Daniel Galvin, however, shows that union influence has remained significant. During the period of union membership decline from 1973 to 2014, states with higher rates of union membership passed more employment laws and created a wider range of rights and protections for workers than states with less of a union presence.

According to Galvin, 90% of U.S. workers do not belong to a union and must look to employment laws to protect their rights instead. But where did these laws come from, and why do some states have more robust regulatory regimes than others?

“I find that unions were largely responsible for their construction,” Galvin said. “Even as they were hemorrhaging members and struggling to survive, they were leading legislative campaigns to create stronger protections for all workers.”

To draw this link between unions and states’ workplace regulations, Galvin conducted a multimethod analysis. First, he examined the relationship between union density—the state’s percentage of nonagricultural workers in a union over each two-year legislative period—and the passage of employment laws in each state.

Second, he used annual Bureau of Labor Statistics reports to create a dataset of every employment law enacted at the state level between 1973 and 2014. He found that states enacted over 6,000 employment laws, with significant variation across states.

Controlling for different trends in states during that timeframe—such as the productivity of state legislatures and economic conditions—he uncovers that states with more union members and lower declines in union density were more likely to pass a greater number of employment laws protecting workers.

And contrary to some previous scholarship, he did not find evidence that more employment laws led to a decline in unions.

Pennsylvania and Maine: Two Outliers

Galvin then turned to two outliers to further explore the statistical relationship: Pennsylvania and Maine. Between 1973 and 2014, Pennsylvania enacted relatively few employment laws despite having one of the highest rates of union membership in the U.S., and Maine passed a large number with an average rate of union membership.

To determine if unions were key players in passing employment laws in these divergent cases, Galvin used a technique called “process tracing,” where he systematically examined evidence of union involvement in multiple employment law campaigns over several decades in both states.

He searched 308 local newspapers in Pennsylvania from 1978 to 2020 and 23 in Maine from 1992 to 2020 that reported on the minimum wage, family and medical leave, workplace discrimination, and employee misclassification, which is when employers mislabel employees as independent contractors.

In Pennsylvania, labor unions were unsuccessful at enacting many laws protecting workers. But Galvin explains that it wasn’t for a lack of effort. In most cases, he finds that Republican Party opposition thwarted the unions’ efforts to advance workplace policies in the legislature.

Maine, however, has some of the strongest employment laws in the country. Galvin shows that organized labor was able to move laws forward in all four policy areas because of its power within the state’s Democratic Party and its ability to form strong policy coalitions with other groups. Unions gained influence in Democratic Party politics after Democratic losses in 1994 when labor leaders became more prominent in its structure and more involved in legislative campaigns.

“Even in these outlier cases, there is voluminous evidence that organized labor was consistently on the frontlines in states pushing for stronger protections for workers—despite their steady loss of members over the years,” Galvin said.

Galvin cautions that unions were not solely responsible for passing these laws, and other factors mattered as well. Still, his current analysis is the first step in supporting the hypothesis that labor unions were integral to building the statutory rights and protections that 90% of all workers—and 94% of those in the private sector—rely on today.

“Notwithstanding their many inadequacies, employment laws constitute some of the only institutional protections workers have left to defend against exploitation,” Galvin said. “Their construction over the last 60 years ought to be considered one of organized labor’s most significant and durable legacies.”

Daniel Galvin is associate professor of political science and an IPR fellow.

Photo credit: Flickr (J. Piette)

Published: August 30, 2022.