Why Do Legislators Reject ‘Half-Loaf’ Compromises?

Get all our news

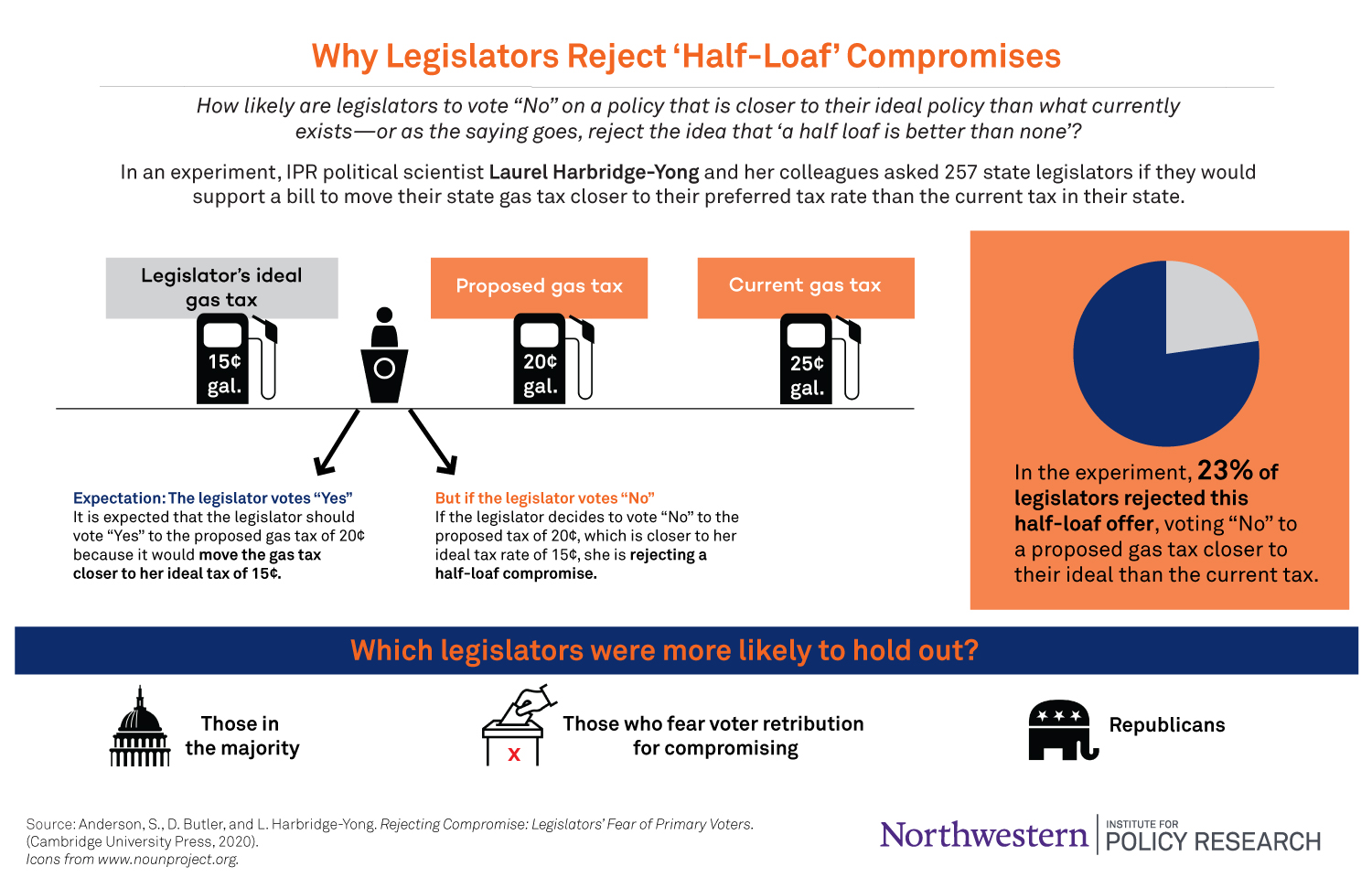

With an approval rating of just 23%, the 116th Congress is viewed negatively by a vast majority of Americans. “Do-nothing Congress” is a frequent complaint heard on television and tossed around on social media and the web. But while many see Congress as gridlocked due to polarization among its members, IPR political scientist Laurel Harbridge-Yong and her colleagues, Sarah Anderson and Daniel Butler, offer an additional explanation: Legislators reject ‘half-loaf’ compromises.

In their new book Rejecting Compromise: Legislators' Fear of Primary Voters (Cambridge University Press, 2020), the researchers show that instead of finding common ground, policymakers might vote “no” even when a policy moves closer to their ideal policy than what currently exists. In other words, they reject the idea that “a half loaf is better than none.”

Gauging how often legislators reject half-loaf compromises across all legislation is nearly impossible to measure in practice since doing so requires mapping the positions of a current policy, a proposed policy, and a legislator’s preference. Yet Harbridge-Yong and her colleagues managed to capture all of these measures by creating a hypothetical voting scenario.

They surveyed 257 state legislators to see whether they might vote “no” on a state gas tax closer to their ideal tax than the current gas tax in their state. Their results reveal that 23% of state legislators surveyed rejected a compromise that moved policy halfway closer to their preferred policy outcome.

Seeking to understand why legislators reject these half-loaf offers, the researchers find that one of the key predictors of rejecting compromise was the perception that voters would punish them for compromising. This fear focused on voters in primary elections. They also show that, in this experiment, Republicans and those in the majority were more likely to vote “no.”

So, while legislative gridlock is widely painted as a result of polarized policy positions that cannot be reconciled, Harbridge-Yong and her colleagues show that gridlock can occur even when a compromise policy is offered, if some lawmakers choose to hold out for the whole loaf.

Laurel Harbridge-Yong is associate professor of political science and an IPR fellow.

Photo by Pixabay

Published: April 1, 2020.