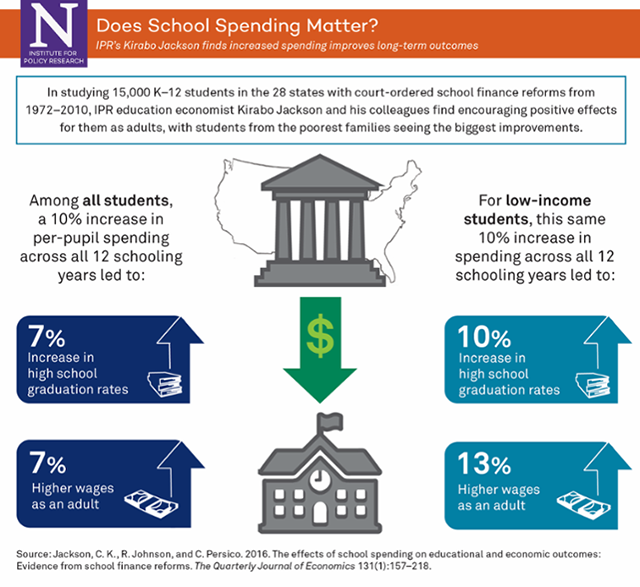

Infographic: Does School Spending Matter?

IPR's Kirabo Jackson finds increased spending improves long-term outcomes

Get all our news

Click on the image above to see a larger version of the infographic.

Whether or not money matters for schools has been a topic of debate for years, beginning about half a century ago with a report ordered by Congress to examine the effect of racial segregation on students.

That report was the first national study to suggest that there is no connection between how much money is spent per student and how well students perform on tests. Since then, the finding has been both confirmed and contradicted in studies conducted by some of the best and brightest researchers in the nation.

A new study, though, by IPR labor and education economist Kirabo Jackson, uses a fresh approach that finds strong ties between spending and results. Published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics, the study tracks large spending increases that resulted from court cases in 28 states between 1971 and 2010.

Jackson, along with the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Claudia Persico (SESP PhD ’16), a former IPR graduate research assistant, and Rucker Johnson of the University of California, Berkeley, finds that in the places where per-student spending rose 10 percent, those students who were young enough to be exposed to these increases for all 12 years of schooling were more likely to graduate from high school and had about 7 percent higher wages as adults. They were also less likely to be poor as adults.

For instance, in 2012, schools spent an average of $12,600 per pupil each year. Jackson’s findings suggest that a permanent 10 percent spending increase—or a permanent increase of $1,260 per student in this example—leads to these improved long-term outcomes.

The results were more dramatic for low-income students, who, on average, spent about six more months in school and earned around 13 percent more at age 40.

How does increased spending lead to these improvements in student outcomes? Jackson and his colleagues discover that the increases in school spending were associated with lower student-to-teacher ratios, longer school years, and increased teacher salaries, which might help to attract and retain more qualified instructors.

The bottom line: “Improved access to school resources can profoundly shape the life outcomes of economically disadvantaged children, and thereby significantly reduce the intergenerational transmission of poverty," Jackson said in an interview with Northwestern's School of Education and Social Policy.

Kirabo Jackson is associate professor of human development and social policy and an IPR fellow.

Published: February 1, 2017.