The History of Abortion Politics

IPR talks with IPR political scientist Chloe Thurston about politicians’ changing views on abortion and the role interest groups play

Get all our news

As interest groups with intense policy preferences on abortion aligned with political parties, those groups helped to pull each party to a more cohesive and consistent pattern of voting.”

Chloe Thurston

IPR political scientist

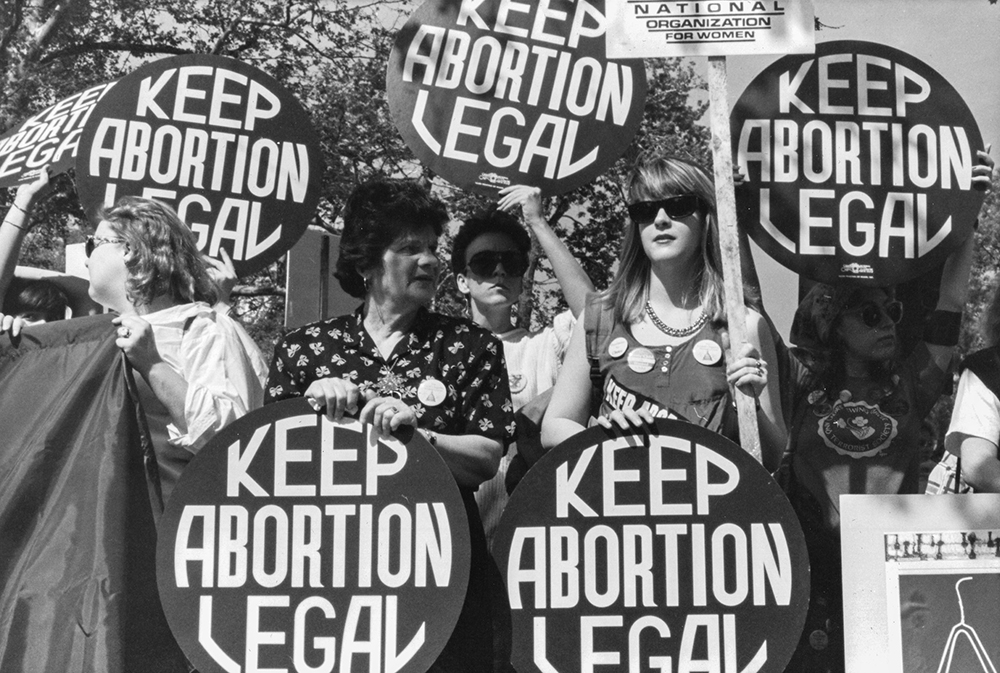

In 1989, pro-choice demonstrators gather outside the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C.

Even before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, abortion remained one of the most polarizing issues among Democrats and Republicans, making it easy to predict politicians’ beliefs about abortion based on their political party. But that wasn’t always true.

A recent study by IPR political scientist Chloe Thurston and David Karol of the University of Maryland examines voting records of California state legislators from the 1960s–1990s to understand the growing ties between the Republican Party and the Christian Right and the Democratic Party and feminist organizations. The researchers show how legislators in California, one of the first states to pass legislation dealing with abortion, shifted from voting on abortion issues based on their religious beliefs to aligning with the emerging views of their political parties.

Thurston discusses the findings of the study, the power of interest groups in abortion politics, and how politicians have changed their views on abortion over time.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What did you find when you looked at voting records of California’s elected officials on abortion between 1967 and 1996?

We looked at voting in the California State Assembly before and after Roe v. Wade (in 1973). In 1967, California became one of the first states to liberalize its abortion law with the passage of the Therapeutic Abortion Act. Before that, abortion was governed by the 1872 criminal code, which outlawed it except in order to save the life of the mother (about thirty other states had similar laws on the books by the 1960s). The Therapeutic Abortion Act extended abortion access to cases where it would protect the physical and mental health of the mother, as well as in cases of rape and incest. Somewhat notably, it was signed into law by then-Governor Ronald Reagan, who would later change his position on abortion.

We examined voting patterns in the State Assembly, which is the lower house of the legislature. At the time that the bill was voted on, the partisanship of the individual legislators was not very predictive of their vote for or against legalization. The issue had not yet polarized along partisan lines. Instead, religious affiliation (namely, whether a legislator identified as Catholic or not) was more predictive. If you think about abortion politics now, if you know that someone in Congress or in a state legislature is a Democrat or Republican, you can predict pretty closely their position on the issue.

We found that over time the effect of religion waned as partisan affiliation came to supplant the role of religion in predicting abortion support. Some of this was due to incumbent politicians shifting their voting behavior, while retirement and replacement of older legislators with those who were more in-tune with their party’s position also played a role.

Can you talk about how interest groups played a role in shifting legislators’ views on abortion from aligning with their religious beliefs to those of their political party?

When we were trying to understand how to characterize that shift, we examined multiple different possibilities. We ultimately emphasize this as a shift from legislators relying on personal background characteristics to decide how to vote, towards relying on the cues sent to them by groups that began aligning with each of the political parties over this time.

As interest groups with intense policy preferences on abortion aligned with political parties—feminist groups with the Democratic Party and evangelical religious groups aligning with the Republican Party—those groups helped to pull each party to a more cohesive and consistent pattern of voting.

Our theory is that [the interest groups] sent new cues to legislators about how they should be voting on that issue, where those cues were absent previously. At the time, of these first votes [in the legislature] prior to Roe v. Wade, abortion was a relatively new issue for voters and legislators, which may have given the latter some leeway in deciding how to vote. But as the issue develops over time, groups and parties may begin to send clearer signals about their policy positions.

What does that say about the power of interest groups over elected officials?

Our paper is looking at a very narrow slice of this question. I would not take our findings to suggest that interest groups are singularly powerful, but our research does provide some evidence in support of the idea that interest groups can contribute to partisan polarization. Polling on the public’s support for abortion is notoriously sensitive to question wording, but that said, the public is generally supportive of abortion access with some restrictions. Interest groups tend to have more extreme preferences than the public on the issues that they do care about. So, this can at times contribute to the support and passage of policies that are more reflective of interest group preferences than broader public ones. This is something that political scientists have found some evidence for outside of abortion policy, for example with gun regulation.

Do you think that there’s room for politicians in our current system who don’t line up with their political party on abortion?

I wrote an op-ed with my co-author David Karol for the Daily Beast a couple of years ago about one of the last anti-abortion Democratic members of Congress, Daniel Lipinski. This was right after he lost his primary election to Marie Newman, who had the support of a number of pro-choice organizations, like Planned Parenthood and EMILY’s List. One could see his loss to a pro-choice challenger as illustrative of the process we demonstrated at the state level in California. Like some of the pro-life California legislators in the 1960s, Lipinski regularly invoked his Catholic faith in explaining his pro-life position. Lipinski’s divergence with his party may have become untenable as the parties’ positioning on these issues has increasingly diverged. However, the Dobbs decision has significantly altered the status quo on an issue where was a substantial amount of public support for the status quo. And moreover, our work on the dynamics of party polarization is a reminder that parties’ issue positions are not static but change over time in response to a variety of factors.

One of the takeaways from your study is that the importance of personal background on a legislator’s vote can vary over time as the state of politics change. How do you see Ronald Reagan’s and Donald Trump’s shifts on abortion fitting into that idea?

It is common for politicians to change their positions on issues. In addition to President Reagan’s reversal on abortion (he later said he made a mistake in signing the 1967 Act as governor), Trump also shifted from pro-choice to pro-life. Biden’s views and positions have also shifted on this issue, from supporting a pro-life constitutional amendment in the 1980s, to pro-choice views in recent decades. Abortion is not special in this regard. Many politicians that previously opposed same-sex marriage now support it.

This points in some sense to the way that politicians are strategic actors, motivated by winning elections and willing to change their positions in pursuit of this goal. But people also just update their views over time, including through learning and experience. If their views are more in line with their constituents’, that may be seen as a positive from the standpoint of representative democracy.

Chloe Thurston is an assistant professor of political science and an IPR fellow.

Photo credit: L. Shaull

Published: August 16, 2022.