News, Entertainment, or Both?

IPR associate Stephanie Edgerly examines how audiences assess what constitutes news

Get all our news

We’re seeing that individual differences matter in how people orient themselves around the concept of news. News doesn’t necessarily look the same for everyone. ”

Stephanie Edgerly

Associate Professor of Journalism and IPR associate

In a media environment where comedians like Trevor Noah host late-night talk shows highlighting news headlines and combative pundits like Tucker Carlson provide commentary while discussing current events, the lines have blurred between news and entertainment.

In a new study, media scholar and IPR associate Stephanie Edgerly and her co-author Emily Vraga of George Mason University, explore how audiences navigate today’s media landscape by conducting two experimental studies asking them to categorize media content.

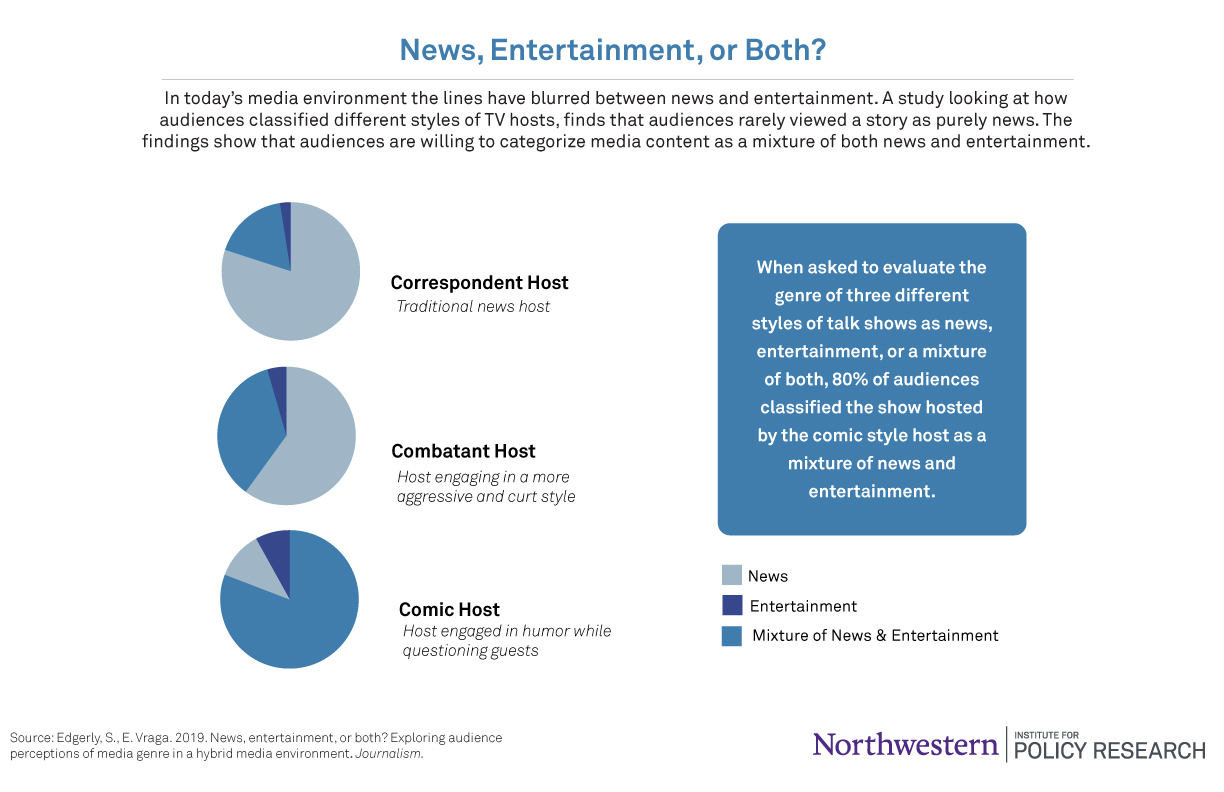

In the first study, they asked participants to watch three separate videos about climate change policy, each featuring a different type of host style: a traditional news correspondent, a combative interviewer, and a comic. Participants then categorized the video segment as news, entertainment, or a mixture of both.

The researchers find that a majority considered the videos with a correspondent host (80%) and the combatant host (60%) as news, while only 11% labeled the video with a comic host as news. Few people considered any of the video versions to be purely entertainment, but 81% of viewers labeled the comic host as a mixture of news and entertainment.

“Just by having a more aggressive talk show host or a comedic talk show host, you get huge swings in whether audiences considered that talk show that they had just watched a segment of to be news, to be entertainment, or to be a mixture of the two,” Edgerly said.

In the second experimental study, the researchers manipulated two aspects of a headline about transgender bathroom policy: the angle of the headline (policy, satirical, liberal confrontational, or conservative confrontational) and the source of the headline (The New York Times, Mother Jones, Drudge Report, or The Daily Show). After viewing the headline, participants characterized the headline on a scale from 1 (entertainment) to 5 (news). According to the authors, this scale captures ratings of news-ness, or the extent to which a specific media message is considered news.

Results indicated that headline angle produced significant differences in ratings of news-ness, with a policy headline rating highest and a satire headline lowest. Edgerly points to a surprising finding regarding headline source: Audiences did not make any meaningful distinction between the “news-ness” of a headline from the mainstream The New York Times, the progressive news organization Mother Jones, and the conservative outlet Drudge Report.

Personal politics also influence how audiences perceived a headline. The researchers looked at how participants from different political parties characterized the headlines. Democrats were more likely to rate a conservative confrontational headline lower in news-ness than a liberal confrontational or a satirical headline, while Republicans rated a policy headline higher in news-ness than a satirical one. Republicans did not rate conservative or liberal confrontational headlines any differently.

“We find initial evidence that people tend to consider a headline that favors their political position to be news and a headline that pushes against their political position to be 'not news',” Edgerly said. She points out that she and her colleague do not believe they have enough evidence from this single study to say that people from one political background are more biased than those from another.

“We’re seeing that individual differences matter in how people orient themselves around the concept of news,” she noted. “News doesn’t necessarily look the same for everyone. What some people consider news, others consider 'fake news'."

Edgerly says that the findings from the study raise two important questions that warrant further research– when do people consider something as news and what does that mean for how we process information?

“We know a whole lot about how journalists define their profession and what journalists think is news,” Edgerly explained. “But there’s really not that much research systematically investigating how audiences are determining what is news and what is not news, especially in a world that pokes at that blurry line between news and entertainment.”

Stephanie Edgerly is an associate professor of journalism and an IPR associate.

Published: October 30, 2019.