CAB 2019: Old Friends and New Ideas

Long-running workshop launches collaborations and discussions

Get all our news

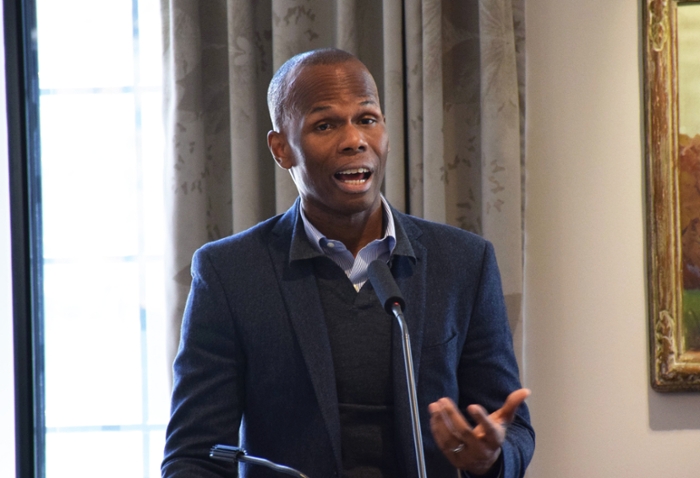

I was looking back at the programs from over the years and the number of people who met here and collaborated—it’s actually quite remarkable.”

James Druckman

IPR political scientist and CAB organizer

IPR political scientist James Druckman, who organizes the annual workshop, welcomed the 2019 CAB participants.

More than 100 scholars and graduate students from the Midwest gathered on Northwestern University’s Evanston campus on May 3 for the 13th annual Chicago Area Political and Social Behavior Workshop (CAB).

The workshop serves as an annual gathering for scholars to share their latest research and for graduate students to meet with mentors in their field.

“I was looking back at the programs from over the years and the number of people who met here and collaborated—it’s actually quite remarkable,” said James Druckman, IPR political scientist and CAB organizer.

Socioeconomic Comparisons and Political Identity

The first speakers of the day, Meghan Condon of Loyola University Chicago and Amber Wichowsky of Marquette University, began attending CAB when they were graduate students at The University of Wisconsin-Madison and have gone on to collaborate as researchers. They presented their forthcoming book, The Economic Other: Inequality in the American Political Imagination (University of Chicago Press). In it, they examine how our social comparisons—how we compare ourselves to others in different socioeconomic classes—affect political identities and demands amid growing income inequality in the United States.

Through experiments, survey data, and the written comments of thousands of Americans, they show that thinking about comparison with the rich and the poor evokes powerful emotions like resentment, anxiety, and scorn. But social comparison does a lot more than that, they said.

Even though the middle class is shrinking, “Americans overwhelmingly see themselves as middle class,” Wichowsky said. “That means many are far off when estimating where they are in the socioeconomic hierarchy.”

That makes people perceive their own status more accurately, even if they don’t learn any new information about inequality or their own position, she said.

Political attitudes change with comparison too; comparison with the rich makes people want government to spend more on social programs to address inequality. Condon noted that “social comparisons can never be stripped of race and gender,” and so a focus on social comparison opens up new ways of thinking about how the politics of economic inequality and identity operate together.

After discussing the importance of social comparison, Condon and Wichowsky showed how several countervailing forces limit social comparison across class lines in America today. As economic gaps widen, growing income segregation and other broad trends increasingly limit Americans’ exposure to people in different classes, making it harder for Americans to use social comparison to make sense of growing inequality and suppressing demands for government to do anything about it, they argued.

Suburbanization and African American Political Attitudes

Reuel Rogers, a Northwestern political scientist, spoke about his research on changes in Black politics and attitudes. African Americans have historically been a reliably liberal group, he said, but in recent years, they have become more moderate and diverse in their politics, particularly around racial issues.

Rogers discussed how Black Americans have been moving from the inner cities to the suburbs, which might account for the shift in political attitudes. As an example, he pointed to how Black suburban residents often held more favorable views of the police compared with Black urban residents.

“Black suburbanites are relativity satisfied with policing in their neighborhoods compared to nearby Chicago,” Rogers said. “They have a lot of skepticism or lack of trust about the police in general but less of that than their central city counterparts.”

Rogers explained that these findings suggest that suburbanization might be an important but understudied source of moderation and diversity in Black attitudes.

Measuring Attitudes Using Dramatizations

Columbia University’s Donald Green spoke about a recent study with his colleagues that uses a novel design to examine the direct and indirect effects of an education-entertainment experiment in Uganda.

Green and his colleagues orchestrated more than 100 local film festivals in rural Uganda and invited nearby villagers to attend for free. During commercial breaks, his team inserted video dramatizations on the topics of violence against women, teacher absenteeism, and abortion—all controversial social issues in the socially conservative country. He cited examples of the country’s conservatism, such as how 75 percent of Ugandan women think it is acceptable for a husband to hit his wife under certain circumstances.

The researchers wanted to see whether the dramatizations had any effect on audience members’ attitudes, and if those attitudes “spilled over” to friends, family, neighbors, or others in the village where the video aired. So why use a dramatization?

“When you are watching a dramatization of a social issue unfolding, you let down your guard and you’re willing to hear the other side,” Green said. “You would normally counter-argue if you believe that, for example, husbands have a right to beat their wives, if you’re just told it’s wrong.”

Green and his colleagues found several instances in which people’s attitudes shifted after watching the dramatizations, but they saw little evidence of spillover effects to others in the villages.

How Listening Can Improve Research

Kathy Cramer of the University of Wisconsin-Madison spoke about the importance of researchers listening to study populations during their research. She detailed how it adds nuance and complexity to the people behind academic studies on public opinion.

Cramer encouraged the researchers in the room to consider incorporating ethnography or one-on-one interviews in their work to observe different worldviews, reveal the way people connect personally to political issues, and draw attention to the people behind political profiles of a typical Republican or Democrat.

“I think it helps to listen to people,” Cramer said. “It helps us to get at this thing I call perspectives. It’s the stuff that helps explain how everything hangs together for people.”

Cramer highlighted her work on the Local Voices Network, an initiative with MIT’s Media Lab and the nonprofit Cortico, to promote discussions about community issues around a “digital hearth,” which are later accessible to journalists, policymakers, and the public.

“Listening is very powerful for helping people understand one another within democracy in general,” Cramer said. “As a scholar of political behavior, it’s been enormously helpful for me to understand the world around me.”

James Druckman is Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science and IPR associate director and fellow. Meghan Condon is assistant professor of political science at Loyola University Chicago. Amber Wichowsky is associate professor of political science at Marquette University. Reuel Rogers is associate professor of political science at Northwestern University. Donald Green is Burgess Professor of Political Science at Columbia University. Kathy Cramer is professor of political science and the Natalie C. Holton Chair of Letters & Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Photos by Meredith Francis and Christen Gall.

Published: May 10, 2019.