Assessing the Bankruptcy Law of 2005

IPR economist Matthew Notowidigdo uncovers costs and benefits

Get all our news

"Targeting is hard, and you might end up doing something that's not that well targeted and then that brings these costs and benefits."”

Matthew Notowidigdo

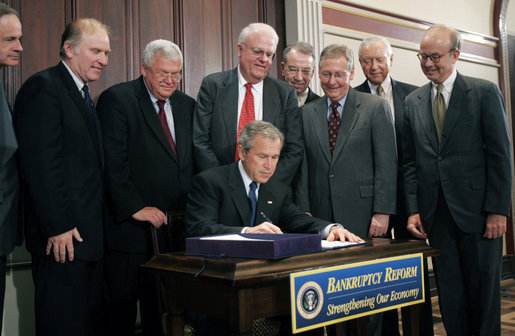

In 2005, Congress passed the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA) after heated debate. The new law was designed to deter people from pursuing bankruptcy by making filing for it more difficult and expensive, as well as less financially advantageous.

To understand what actually happened when the Bankruptcy Act was implemented and shed light on the debate between those who supported and opposed the law, IPR economist Matthew Notowidigdo and four colleagues compare bankruptcy filings in the two years before and after the law took effect.

Proponents of the 2005 Bankruptcy Act argued that too many people who could pay their debts were taking advantage of the system by filing for bankruptcy, and that bankruptcies made consumer credit more expensive. Fewer bankruptcies would make consumer credit cheaper.

Critics of the law maintained that limiting access to bankruptcy would harm struggling families facing crippling medical debt or other catastrophes, as well as enrich powerful financial interests.

Two contenders in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary continue their disagreement over the 2005 law: Former Vice President Joe Biden was a strong supporter in the Senate when the bill passed, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard law professor in 2005, entered the political arena in her adamant opposition to it.

“What really inspired us was actually the work by Sen. Elizabeth Warren,” Notowidigdo said. “She was one of the first professors to survey bankruptcy recipients, . . . and we thought that we could bring in economist tools to study the same question.”

The economists wanted to know two things about the law’s results: First, did lenders have more money available to borrowers at lower interest rates if there were fewer bankruptcy filings? This was the proponents’ argument. Second, did the law target bankruptcy “abusers” who manipulated their assets and gamed the system—or did it hurt people who needed bankruptcy after suffering financial disasters such as hospitalizations, accidents, or divorce, as opponents predicted?

In their recent working paper, the researchers show that the law cut the rate of household bankruptcy filings in half. There were about one million fewer filings in the two years following it than otherwise would have occurred under the old system.

Notowidigdo and his co-authors also determine that the 2005 Bankruptcy Act lowered interest rates. Credit card companies, they estimate, passed through between 60 and 75% of their savings from the reduction in bankruptcy write-offs to consumers.

“I think we find evidence that interest rates decline when you make it harder to file for bankruptcy. This is what the proponents of the reform had expected. But it's not like BAPCPA succeeds on all counts,” he noted.

The authors find that people at middle- and lower-income levels were deterred from filing for bankruptcy, so the drop in interest rates was not a result of higher-income people declaring bankruptcy to avoid their consumer debt, as intended by the act’s creators.

“In contrast to what the proponents probably would have wanted, we didn’t find any evidence that the reductions were well-targeted,” Notowidigdo said.

A particular area of debate over the 2005 Bankruptcy Act is its impact on people who struggle with large loads of medical debt. Notowidigdo and his colleagues, using data from California he analyzed in earlier work, demonstrate that the rate of bankruptcy filing following an uninsured hospitalization dropped by 70% after the law was implemented.

Notowidigdo hopes the research reaches policymakers.

“The message that we try to deliver when we talk to the policy community is that targeting abuse is a good idea,” he said, “but in practice that targeting is hard, and you might end up doing something that's not that well targeted and then that brings these costs and benefits.”

Matthew Notowidigdo is an associate professor of economics and an IPR fellow. His research appears in “The Economic Consequences of Bankruptcy Reform,” IPR Working Paper 19-24.

Photo: George W. Bush White House Archives.

Published: December 16, 2019.