The Changing Safety Net for Children

IPR director finds 80 percent of safety net spending has shifted to families with earnings

Get all our news

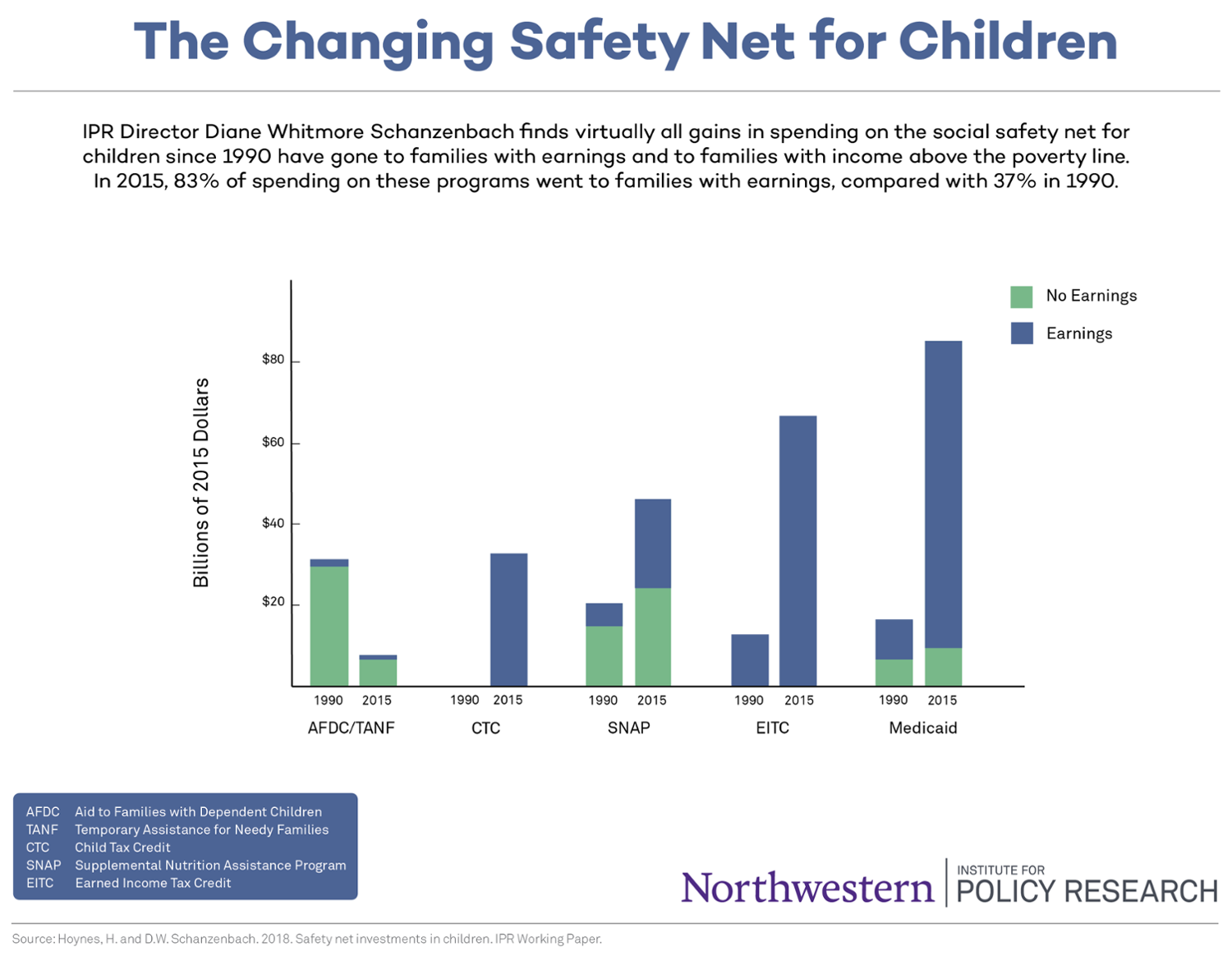

Click on the image above to see a larger version of the infographic.

Five states now require that Medicaid recipients work, which has cut benefits for tens of thousands of people. As another 11 states await federal approval to impose similar work requirements, new Northwestern research points to how safety net programs are “extremely effective at reducing poverty,” according to economist and IPR Director Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. She also finds that changes in government spending might harm the poorest children.

Schanzenbach and Hilary Hoynes at the University of California, Berkeley are the first to use administrative data to examine four core safety net programs that combat child poverty:

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

- Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC)—now called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

- Medicaid

These four programs combined remove 7.4 million children from poverty in 2016, with another 11 million remaining mired in poverty.

The administrative data allow the researchers to pinpoint the change in these programs’ spending over time. While their research shows the United States is spending more on safety net programs today than it was 25 years ago ($200 billion combined in 2016)—they have also identified a large shift in which households receive benefits.

Much more assistance now goes to households with earnings—where people work—than to the poorest households without earnings. Over this period, all increases in spending have gone to families with earnings at or above the poverty level. Eighty percent of safety net spending now goes to families with earnings.

This move to work-contingent assistance is problematic, Schanzenbach noted.

“These shifts in safety net spending we have observed may have lasting negative effects on the poorest kids in this country,” Schanzenbach said in a recent IPR colloquium. “The poverty rate for children is 17.5 percent in this, the richest of nations.”

Also, the researchers point to how the United States ranks near the bottom of the 37 OECD nations in terms of government spending on children. Such assistance has remained flat over the last two decades at around 2 percent of U.S. GDP, while per capita spending on the elderly has grown over the same time and now stands at 9.3 percent of GDP.

Schanzenbach pointed to the “credible and compelling” evidence that these safety net programs lead to genuine improvement in people’s lives—in their health, education, and economic wellbeing. These effects have only recently been quantified, and many benefits remain hard to measure and could take years to appear.

The safety net also leads to economic benefits for the country, including increased tax receipts and greater human capital.

But Schanzenbach emphasized that beyond the economic benefits of funding these programs, there are moral reasons to provide a safety net for children in poverty.

“We would absolutely not want to think about the safety net as only an investment,” she said. “We also think that there is some shared humanity.”

Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach is IPR director and the Margaret Walker Alexander Professor. Read more about the study here.

Published: December 20, 2018.