Faculty Spotlight: Joseph Ferrie

IPR associate Joseph Ferrie mines historical data for contemporary policy insights

Get all our news

To many, the 1918 flu pandemic that killed more than 50 million people around the world is a distant chapter of history. To economist and IPR associate Joseph Ferrie, this historical event offers a way to gain insight into today’s policy questions.

Economist and IPR associate Joseph Ferrie says history provides a "laboratory" for contemporary policy issues.

“History provides crazy natural experiments,” Ferrie said.

About 10 years ago, Ferrie became interested in a new area of economic research looking at how early life influences can affect later outcomes, such as earnings and education. But he recognized the limitations of following a group of participants from birth to old age.

“The problem is one of mostly logistics,” Ferrie said. “It’s prohibitively expensive …. You would never get permission to run experiments like these.”

Instead, Ferrie uses historical data, including World War II enlistment records and 20th-century census data, to answer questions that still exist today or are not ethical to study. In studying children in utero during the pandemic a century ago, for instance, he found fewer of them graduated from high school, likely affecting their wages and jobs as adults.

Childhood Lead Exposure

Though Americans’ health and standards of living have improved, the effects of lead in water are as dangerous now as they were before the turn of the century. Ferrie mined 50 years of data, originating in the 1890s, to reveal lifelong effects of childhood lead exposure, with implications for Flint, Michigan, and beyond.

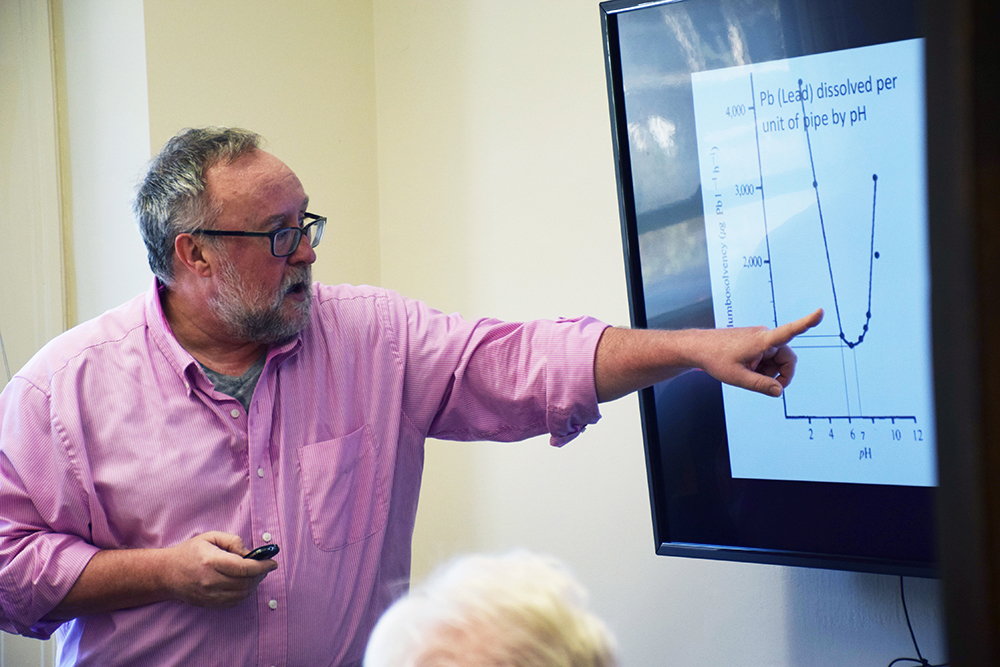

Ferrie first linked individuals to their place of birth, allowing him to approximate their lead exposure based on each city’s piping material and water pH. He then linked that data to later records for the same individuals outlining occupation, education, and more.

With an incredibly detailed dataset of 1.2 million people, Ferrie discovered that lead has severely impacted the human capital of generations of Americans. Adults exposed to lead in their drinking water as children made less money and had lower IQ scores.

Lead also contributes to diseases that develop decades later. Ferrie is now finding that late-onset Alzheimer’s, which does not appear to have a strong genetic component, is tied to environmental exposure.

“This isn’t just a historical exercise,” Ferrie said. “There are still many birth cohorts that were exposed to lead through their drinking water that are not yet even retired.”

He suggests that historical data could allow researchers to better track projected rates of late-onset Alzheimer’s.

Nuclear Fallout

A study exposing millions of Americans to nuclear radiation is unethical and would never be approved. But the government carried out aboveground nuclear tests in the 1950s that spread radioactive material across the country from the test sites in Nevada all the way to Maine.

Ferrie is combining nuclear fallout maps with school testing data from 1965 to determine if cognitive development was affected by in utero exposure to nuclear fallout. Data from Sweden after the Chernobyl accident have shown substantial effects, particularly on IQ.

“This is not as immediately policy relevant because we’re not suddenly going to go back to a program of aboveground nuclear testing,” Ferrie said, “but it does provide information on the frailty of certain processes that take place in utero.”

Universal Preschool

History can also inform us about how programs targeting children can improve later-life outcomes, according to Ferrie. He is outlining the benefits of universal preschool, based on a federal program during World War II.

In 1943, women worked in factories while the men were away at war. But with mothers away at work all day, someone needed to take care of their children.

The federal government decided to fund universal preschool programs in towns with high demand for labor, establishing thousands across the country. Not every town had a preschool, though, setting up a natural experiment of kids who went to preschool versus kids who did not.

Ferrie has followed the preschool-educated children to the 2000 Census and the American Community Survey in 2001, with plans to continue gathering data. He has found dramatic positive effects of preschool on educational attainment and adult income.

Ferrie noted that previous cost-benefit calculations have discovered a 9–16 percent rate of return for each dollar invested in early life education. He believes that his work could help reveal more positive effects.

“If you’re only observing kids up until they become older adults—in their 50s—you’re probably understating some of the additional benefits,” Ferrie explained. “Those cost-benefit ratios may be considerably different.”

Ferrie stressed that current studies cannot provide the same kind of longitudinal data on such a large population.

“History provides this laboratory,” Ferrie said. “It’s a particularly useful lens on contemporary policy issues.”

Joseph Ferrie is professor of economics and an IPR associate.

Published: November 1, 2018.