Study Links Violent Crime to Less Sleep, More Stress in Children

IPR's Jenni Heissel and Emma Adam find proximity to crime disrupts sleep patterns

Get all our news

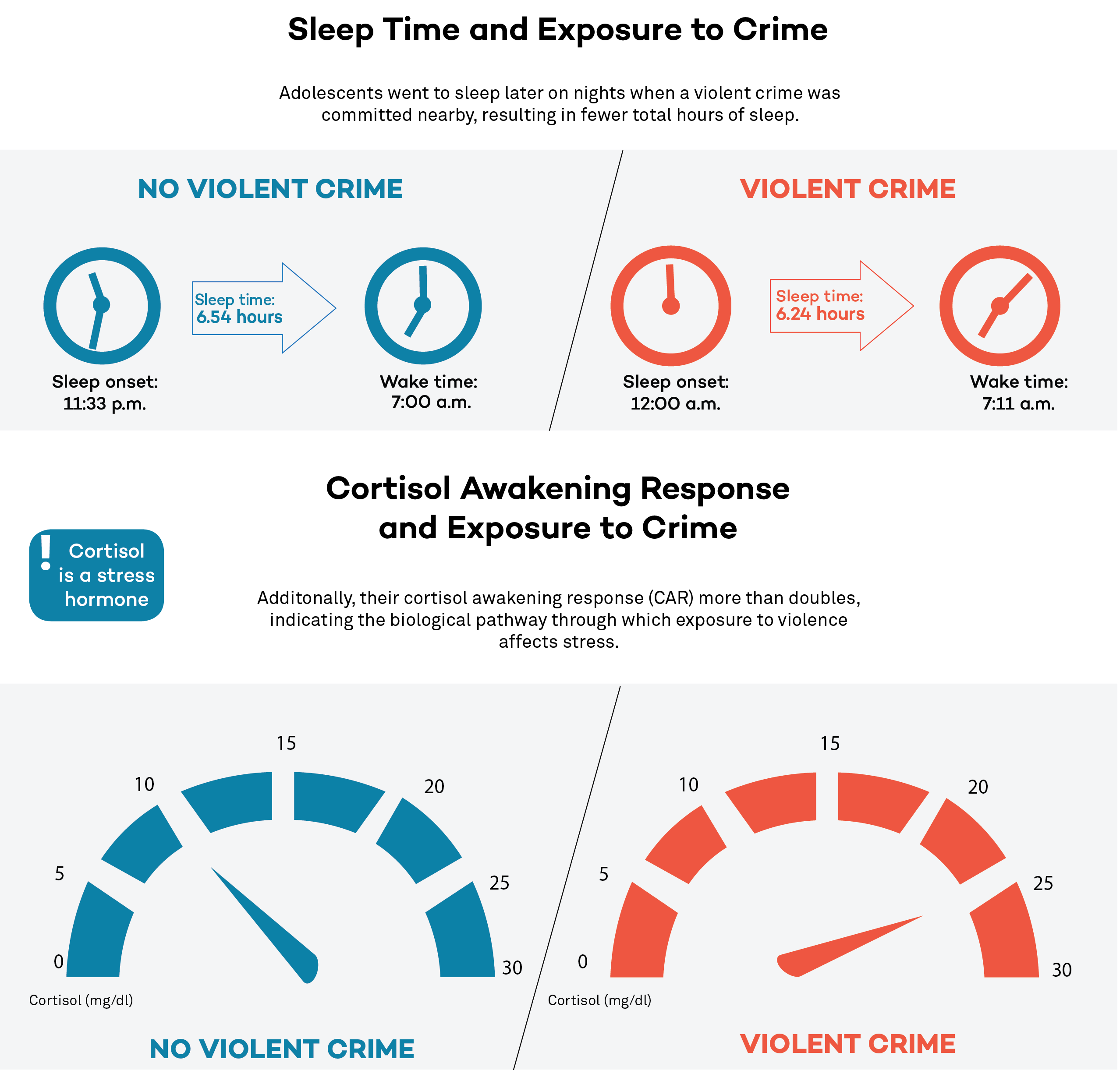

Now, recent Northwestern University research published in Child Development suggests sleep disruption following violent incidents and increased amounts of the stress hormone cortisol offer a biological explanation for why children who live in neighborhoods with higher rates of violent crime struggle more in school.

Click on the image above to see a larger version of the infographic.

“Both sleep and cortisol are connected to the ability to learn and perform academic tasks,” said study lead author Jenni Heissel, former IPR graduate research assistant. “Our study identifies a pathway by which violent crime may get under the skin to affect academic performance.”

The study, conducted by researchers at Northwestern, New York University, and DePaul University, found that violent crime changes the sleep patterns of children living nearby, which increases the amount of the stress hormone cortisol in the child’s body the day immediately following the violent incident. Both sleep disruption and increased cortisol have been shown to negatively impact how a child performs in school.

“Past research has found a link between violent crimes and performance on tests, but researchers haven’t been able to say why crime affects academic performance,” Heissel said.

Researchers tracked the sleep and stress hormones of 82 young people, ages 11 to 18, in a large Midwestern city who attended public schools that were racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse.

The students filled out daily diaries over four days, wore activity-tracking watches that measured sleep and had their saliva tested three times a day to check for cortisol. Researchers also collected information on all the violent crimes reported to the police in the city during the study, including which youth had a violent crime occur in his or her neighborhood.

For each youth, researchers compared the students’ sleep on the nights following a violent crime to their sleep on nights when there were no violent crimes committed nearby. They also compared students’ stress hormones (cortisol) on days following a violent crime to their stress hormones on days when there were no violent crimes committed nearby.

Among the findings: Youth went to sleep later on nights when a violent crime occurred near their home, often resulting in fewer total hours of sleep. In addition, the increase in youth’s cortisol levels the morning after a crime occurred nearby the day before was larger than on mornings following no crime the previous day, a pattern that previous research suggests might reflect the body’s anticipation of more stress the day following a crime. The changes in sleep and cortisol were largest when the crime committed the previous day was a homicide, moderate for assault and sexual assault, and nonexistent for robbery.

“The results of our research have several implications for policy,” suggested IPR developmental psychobiologist Emma Adam, co-author of the study. “They provide a link between violent crime and several mechanisms known to affect cognitive performance."

In addition, "they may help explain why some low-income youth living in high-risk neighborhoods sleep less than higher-income youth," Adam added. "They suggest that although programs to reduce violent crime may be the best policy solution, schools could also provide students with programs or methods to cope with their response to stressful events like nearby violent crimes.”

The study, "Violence and Vigilance: The Acute Effects of Community Violent Crime on Sleep and Cortisol" was supported by Northwestern's Institute for Policy Research and the National Institutes of Health.

Emma Adam is professor of human development and social policy and an IPR fellow.

This article was originally published by the School of Education and Social Policy.

Published: January 17, 2018.