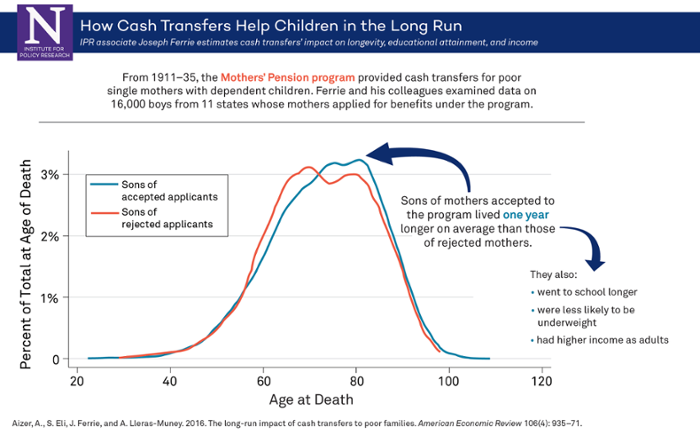

Infographic: How Cash Transfers Help Children in the Long Run

IPR associate Joseph Ferrie finds cash transfers add 1.5 years of life

Get all our news

Click on the image above to see a larger version of the infographic.

A century ago, a remarkably successful cash transfer program began providing money to mothers in need, increasing their sons’ life spans by about a year, according to research by economist and IPR associate Joseph Ferrie.

“In terms of longevity research,” Ferrie explains, “this is a shockingly large number.”

The program’s effects on the poorest families was even more dramatic: Boys in those families lived one and a half years longer than those whose mothers did not qualify for the program.

The Mothers’ Pension Program was the first government-sponsored welfare program in the United States. Running from 1911–35, the program’s cash transfers typically made up between 12 and 25 percent of a family’s income and lasted for around three years.

In the American Economic Review, Ferrie and his colleagues undertook a massive task to match the program data to census, World War II, and death records. The dataset included more than 16,000 boys from 11 states whose mothers applied to the Mothers’ Pension program. The researchers were unable to examine outcomes for women, who could not be followed due to the name changes that occurred through marriages, nor did the datasets contain enough information to include African-Americans.

Ferrie and his colleagues also investigated how exactly the program could have increased longevity. They found that cash transfers reduced the probability of a child being underweight, increased educational attainment, and increased income in early adulthood—all mechanisms for longer lives according to previous research.

“Public policy today can learn from the past,” Ferrie pointed out.

He is currently examining a federally funded preschool program that began during World War II, offering childcare to encourage women to go to work in factories. Ferrie and his colleagues are following these children over the course of their lifetimes and finding similar positive effects.

These historical results demonstrate the value of early-life interventions, a current focus of investigation by many of IPR’s experts, including biological anthropologists and developmental psychologists, in addition to economists. Their findings are adding to the pioneering work of Nobel economist James Heckman at the University of Chicago, who has found that interventions in the preschool years are cost-effective, leading to higher adult income, better health, and lower rates of incarceration.

“Something as simple as providing money to families that are in obvious need has many of the same kinds of significant positive effects,” Ferrie said.

Joseph Ferrie is the Fitzgerald Professor of Economics History and an IPR associate.

Published: November 17, 2017.