Living on Less than $2 a Day

Johns Hopkins sociologist recounts how 'death of welfare' led to rise in extreme poverty

Get all our news

Kathryn Edin recounts the day-to-day struggles of the extreme poor, who live on less than $2 a day.

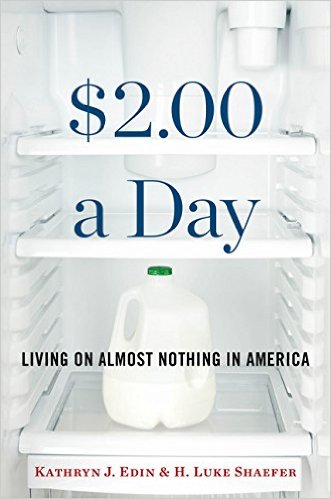

It was opening a refrigerator in a bare, rundown apartment and seeing nothing but a milk carton that provided the inspiration for the cover of Kathryn Edin's latest book, $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America.

That lone milk carton became symbolic of everything the book was about, said Edin, a Johns Hopkins sociologist and Northwestern alumna (PhD, ’91), in her February 18 IPR Distinguished Public Policy Lecture at Northwestern University.

“Could it be that in the aftermath of welfare reform, a whole new kind of poverty had arisen in the United States—a poverty so deep, we hadn’t even thought to look for it?” she said as she dove into her study of the more than 1.6 million Americans who now live in extreme poverty in “the world’s most advanced capitalistic society.”

Edin recounted the day-to-day struggles of those who live on less than $2 a day—of getting fired because your roommate used all the gas in the car tank so you had no way to get to work, of standing in line to sell your blood plasma twice a week to generate much-needed cash, and of being so hungry that it made you feel “like you want to be dead,” as 18-year-old Tabitha told her, “because it’s peaceful being dead.”

She zeroed in on this extreme poverty in America after spending a summer in Baltimore conducting a study on young people born in public housing. What she saw led her to the larger question of how does one end up in this kind of extreme poverty—and what do you do to survive?

Edin spent part of her early career at Northwestern University, where she was an IPR fellow from 2000–04.

“Her foundation for research was born at both Northwestern and IPR,” said IPR Director David Figlio, an education economist, in introducing her to the 90-plus attendees. “It’s difficult to think of a more important research question than the line of work that Kathy does.”

The 'Death of Welfare'

The book dissects the national data on the larger trend, with statistics from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, but it also recounts what she and her research team, including her co-author H. Luke Shaefer of the University of Michigan, found when they went to Chicago; Cleveland; Johnson City, Tennessee; and two small towns along the Mississippi Delta, seeking out people in extreme poverty and listening to their stories.

The people they met are part of a larger trend: Data shows extreme poverty in the U.S. has increased since the passage of welfare reform in 1996. About 600,000 families with children lived on less than $2 per person per day in 1996, growing to more than 1.6 million families in 2011. Meanwhile, food bank usage has increased and the number of homeless students has risen. The United States has also become the world’s leading supplier of blood plasma, with the donations the only source of cash income for some of the country’s poorest citizens.

Edin pinpoints the “death of welfare” as one cause behind the increase, explaining that welfare has become “a shadow of its former self” since reform.

In 1994, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program served 14.2 million people. Today, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which replaced the AFDC, serves about 4.1 million people, a drop of 71 percent. The enactment of welfare time limits has contributed to the drop: The 1996 welfare law prohibits states from using federal TANF funds to aid most families for more than 60 months.

The death of welfare may have led more people into poverty, but there are also factors keeping them there, including unsafe work conditions, insufficient work hours, wage theft, and labor law violations.

(right), IPR graduate research assistants, and

postdoctoral fellows.

Edin told the story of a woman who found a job cleaning foreclosed homes in the winter in Chicago. The mold in these homes and the chemicals used for cleaning weakened her immune system, leading to a cycle of illness and missed work. Her employer then branded her unreliable and cut her hours. The woman ended up quitting to find more stable work, but she couldn’t find a new job and ended up homeless.

Those living on less than $2 a day also have to worry about unsafe conditions at home, dealing with housing instability and sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. One woman was “doubling up” with family because she couldn’t afford a place on her own, and she came home from work to find her uncle molesting her 9-year-old daughter.

Pinpointing Potential Solutions

With such a variety of factors contributing to extreme poverty and keeping people from breaking free of its cycle, what can policymakers do?

Edin suggests that there needs to be a cash safety net, because “we can’t completely rely on a work-based safety net.”

“We really do need something to catch people when they fall,” Edin said. “The help for the working poor only applies to them when they are working. When they lose those jobs, they have nothing.”

She highlighted possible solutions such as reviving the welfare system, offering a guaranteed child allowance, or expanding the childcare tax credit. Edin also argued everyone deserves the opportunity to work. Everyone she spoke to said they wanted more work, “Nobody said they wanted more handouts,” she noted.

Most importantly, Edin proposed a litmus test for any proposed reform: “Does it integrate the poor, does it weave them back into society, does it give them honor and dignity? Or does it separate them, shame them, stigmatize them?”

“When we integrate the poor and give them dignity, we have a better chance of getting them out of poverty,” Edin concluded.

Kathryn Edin is Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Sociology and of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health at Johns Hopkins University.

Published: March 29, 2017.