Back-of-the-Envelope Estimates for Better Policy

IPR associate Seth Stein draws a line between Fermi estimates and policy decisions

Get all our news

Can "quick-and-dirty" calculations make for better public policies?

What do earthquakes and water heaters, and bathtub spills and terrorist attacks, have in common? They concern policy issues that can be evaluated with a Fermi estimate, according to geophysicist and IPR associate Seth Stein.

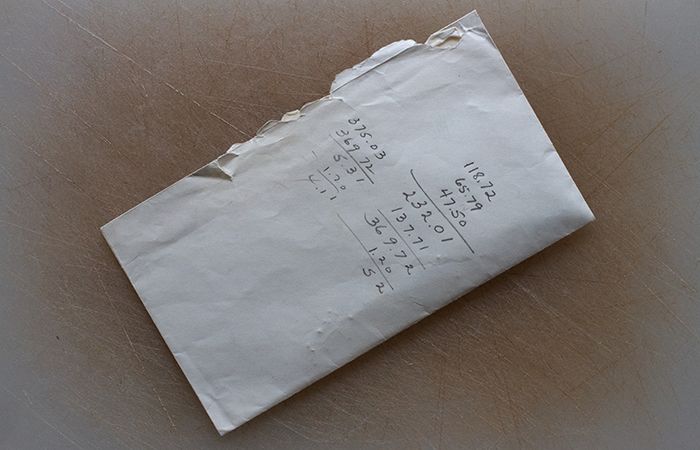

Named for nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi, these “back-of-the-envelope problems” are meant to be solved quickly—with little data and some good analytic reasoning.

“You start with a problem where you say, ‘I have absolutely no idea,’” Stein explained, “and then you start breaking it down.”

For example, in 1945 Fermi famously estimated the strength of the first U.S. atomic test explosion by gauging how far paper traveled when he dropped it at the moment of the blast. President Barack Obama also recently used a Fermi estimate to underscore that Americans are more likely to die from a bathtub fall than from a terrorist attack.

Stein’s class on natural hazards and decision-making has done the same thing with a local example: In February 2015, the Illinois Emergency Management Association (IEMA) encouraged state residents to secure their water heaters, noting that earthquake shaking can cause water heaters to fall, which could cause a house fire.

Though it makes sense for an earthquake-prone state like California, which has had this policy in place since 1991, does it make sense in Chicago?

Stein, IPR graduate research assistant Edward Brooks, and the other students in the class started their Fermi estimation with a cost-benefit analysis: How likely is it that Chicago will experience an earthquake large enough to topple water heaters? In other words, is it worth spending around $150 to secure your water heater if you live in the Windy City?

Because there are no known cases of strong earthquake shaking in Chicago, they combined 200 years’ worth of past Illinois seismic data with that on earthquakes damaging water heaters in places such as Santa Cruz, Calif.

"The chance of earthquake shaking strong enough to damage water heaters is very small, and we found no cases of earthquake-toppled water heaters in Illinois," Stein explained, noting that "spending the same money on a lottery ticket when the jackpot is large would be a better investment" than securing a water heater in Chicago.

So why did the IEMA tell Illinois residents to secure their water heaters?

Policymakers often err on the side of caution, Brooks said. Though the probability of a big earthquake hitting Illinois might be “miniscule,” he explained, the “repercussions” of failing to warn residents would outweigh the “abundance of caution” shown if a damaging earthquake were to hit the state.

For Stein's class, the exercise illustrated a hole in how policymakers make decisions—not just around the issue of water heaters or even natural hazards, but around public policies in general.

“If we look at the vast majority of policy decisions that governments make, very rarely do they consider the costs and benefits,” Stein said.

An exercise like this shows how a “quick-and-dirty” Fermi estimate can give meaning to policy decisions, Brooks concluded.

Seth Stein is William Deering Professor and an IPR associate. Edward Brooks is an IPR graduate research assistant. Both are in the department of earth and planetary sciences. Their article was published in Seismological Research Letters.

Top photo: Alan Levine, Flickr

Published: April 26, 2016.