Learning How to Think About Experiments

IPR’s James Druckman distills his knowledge, arguing for a slower approach to their design and use

Get all our news

Experiments are not a final word. They’re a part of the construction of a knowledge base.”

James Druckman

IPR political scientist

A century ago, political scientists understood their discipline as an observational science—not an experimental one. Today, experiments have become central to political science as they have for all the social sciences. Technology enables unprecedented data access and analysis, and the “open science” movement is leading to more transparency and replication work.

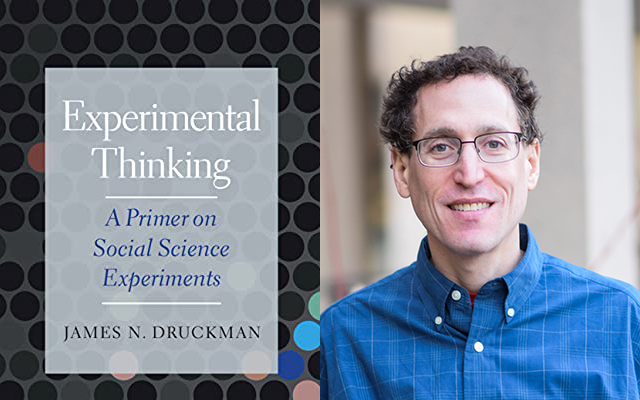

A pioneer in the use of experiments in political science, IPR political scientist James Druckman introduces, defines, and explains experimental thinking for students and practitioners across the social sciences in his recent book, Experimental Thinking: A Primer on Social Science Experiments. His training in experimental social science began in the 1990s. In 2009, he led one of the first conferences on the topic devoted to political science applications, which led to the first Cambridge Handbook of Experimental Political Science. His expertise informs the book’s purpose and approach.

Druckman says he learned to think experimentally from his parents, to whom he dedicates the book. He recalls working on experimental research as an undergraduate at Northwestern for his father, Daniel Druckman, a social psychologist at the University who was a student of Donald Campbell, a methodological trailblazer in the social sciences. Campbell and IPR sociologist and fellow emeritus Thomas D. Cook wrote the influential Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings (1979).

“I think that became a natural way to think about things to me,” Druckman said, adding that his mother, Marj Druckman, taught him how to “persevere through challenges and complex situations, which I think is crucial in designing experiments.”

The book’s aim, Druckman writes, “is to provide readers with a way to ‘think’ about experiments, both as users and as consumers.”

Social science experimentation may result in productive analysis for understanding causal connections and informing policy. However, Druckman cautions, slower and more careful design and use of experiments are critical in a world of easily accessible data and powerful computing.

Experimentation today, he explains, is characterized by the huge growth in new data sources, the availability of new methods of measurement, experiment design, and statistical analysis. More disciplines have begun using experiments. But the rapid and easy access to experiments has led to problems.

“As tools become available more and more quickly, people are apt to jump on them. People are kind of quick to try to draw inferences directly to the political or social or economic world,” Druckman said. “You have to be really careful in any one particular study. … People are always trying to find a single study and then drawing big inferences from it.”

Druckman recommends that his readers begin by considering experimentation as a part of the larger scientific questions they want to answer rather than focusing on details of design such as sampling.

Researchers should view experiments “as a part of the scientific process,” he explained. “You have to get to the experiment after you go through many other steps, … rather than trying to jump to data collection very quickly, which I think is an urge now that you can get data quickly.”

Although he urges deliberate care in social science experimentation, Druckman—as is clear from his own valuable work—sees great promise in it.

He notes that the common criticism that experiments are artificial and may not reflect how “real” people behave is flawed. Social science experimentation is meant to isolate the effect of a variable, not mimic reality, he contends.

“Experiments are not a final word. They’re a part of the construction of a knowledge base,” he said. “Instead of dismissing experiments, appreciate what they are offering and take any critiques you have about a particular study and think about what you can do with those critiques to fill in the gaps that might be questionable.”

James Druckman is Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science, IPR associate director, and an IPR fellow.

Photo credit: Cambridge University Press

Published: December 15, 2023.