Communicating Science in a Politicized Era

IPR political scientist identifies hurdles, antidotes for scientists and public

Get all our news

The bottom line is that basic human psychology and the nature of politics makes effective scientific communication difficult”

James Druckman

Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science and an IPR fellow

IPR political scientist James Druckman examines public opinion on seemingly controversial scientific topics.

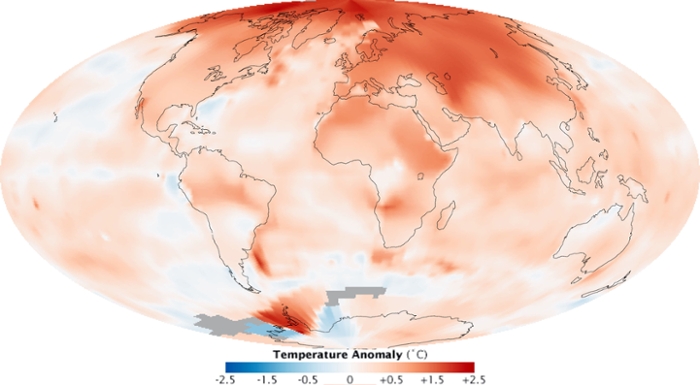

“When it comes to climate change, there’s about as much of a scientific consensus as you can get,” said IPR political scientist James Druckman. Yet a clear partisan divide exists, with about half of the U.S. public believing that humans are the primary drivers of climate change and the other believing that it is a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Druckman has been studying public opinion on climate change to understand the hurdles and antidotes to effectively communicating information on seemingly controversial scientific topics. In doing so, he seeks to answer key questions of how researchers and policymakers can help the public to better understand science and related policies.

“There seem to be approaches to improving scientific communication,” Druckman said at a December 9 Northwestern alumni event. “But there are also many challenges.”

Drawing on several of his recent studies, he identified three key challenges to this “complex problem”: a tendency to rely on irrelevant or inaccurate information, partisan polarization, and the politicization of science.

A reliance on inaccurate information

Druckman began by demonstrating a general tendency for people to reach a misinformed conclusion due to their reliance on the most accessible or immediate information they have. In a study published in Nature Climate Change, Druckman found individuals based their belief about climate change on the temperature that day—which in the experiment was 10 degrees higher than normal.

“As people think today is warmer, they become more believing in global warming and more likely to worry about global warming,” Druckman explained. “The concern here is that people are not thinking about climate in a longer range of patterns, but just kind of flipping around based on whatever the temperature is today."

In the experiment, he was able to mitigate this “local warming effect” by prompting respondents to consider the weather over the entire year. Inducing individuals to think about longer-term climate reduced reliance on the temperature from a particular day. This nudge also endured for at least some time, with a replication study finding the corrective prompt continued to affect beliefs seven days later.

The key for scientists here, Druckman said, is to use language that minimizes “attribution substitution,” where people believe the information most readily available in their mind no matter how relevant (or not) it is to the topic—which in this case means prompting people to think about temperature changes over time rather than for just one day.

Partisan polarization

“Democrats and Republicans seem quite far apart on a lot of issues, including scientific ones,” Druckman said. He explained this occurs because people tend to seek out information that confirms their partisan beliefs. They also typically view evidence consistent with their partisanship as stronger.

In a survey about the 2007 Energy Act, which had bipartisan support, Druckman, IPR social policy expert Fay Lomax Cook, and Toby Bolsen, a former IPR graduate research assistant now at Georgia State University, found respondents increased their support for an issue when told their political party endorsed it. When the endorsement came from the opposite party, however, their support for the issue dropped.

Yet the study also shows it is possible to overcome such partisan reasoning by asking respondents to justify their opinions. Fostering more in-depth discussion prompts people to think about how accurate a party’s position is on a given issue, Druckman said.

The politicization of science

More than 97 percent of scientific studies on climate change endorse the idea that humans are causing global warming. But even when people learn of this consensus, their opinions do not consistently change to align with the evidence.

In an IPR working paper, Druckman examined how political party affects whether people agree with the scientific consensus. Working again with Bolsen, he asked more than 1,300 randomly selected participants from across the political spectrum to what extent they think humans cause climate change versus to what extent they think it results from natural changes.

The two researchers then provided one group of respondents with “consensus information” from a report produced by more than 300 respected climate scientists and reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences. It concluded that climate change is “primarily due to human activities.”

In addition to the consensus information, another group received a statement that added politics to the discussion. It noted the role that humans’ actions play in driving climate change has been “a point of debate,” and politics “nearly always color scientific work with advocates selectively using evidence.”

The consensus information did not lead all participants to higher levels of belief in human-induced climate change, Druckman and Bolsen discovered. In fact, for Republicans with higher-than-average political and scientific knowledge, the consensus information actually drove down their beliefs that human activity is fueling climate change.

“As a high-knowledge Republican, you know where a lot of elite Republicans stand, and you probably have a strong prior opinion on climate change,” Druckman explained.

Republicans with less knowledge of politics and science, meanwhile, increased their belief in human-induced climate change after reading about the expert report. This was also true for both more and less knowledgeable Democrats.

“The bottom line is that basic human psychology and the nature of politics makes effective scientific communication difficult,” Druckman explained. “That said, there are approaches to enhancing the impact of science on public opinion. Identifying these approaches is critical for the advancement of science and society.”

James Druckman is Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science and an IPR fellow.

Watch the webinar.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Published: January 27, 2017.